Modern concepts in longsword fencing

The following text deals with the theory of fencing from a modern point of view and is primarily intended for referees, fencing coaches but also fencers who need to think about fencing more analytically. Ultimately, however, I find it useful for all advanced swordsmen to be familiar with the following terms and concepts, which could also help to clarify and improve the public debate.

Introduction

Definitions in fencing are here to describe particular situations or behaviour of fencers (conscious or not). They often have blurred boundaries and do not imply universal laws. Fencing, despite centuries of systematisation efforts, is not an exact science. Some methods and principles usually bring fencers who practice them an advantage. However, there is always some “but”. There is no ultimate advise which true under all circumstances. Every situation has too many input variables to predict its outcome. Out opponent is often an unknown personality, and violating predictability is one of the necessary skills in fencing. Subtle common mistakes also contribute significantly to the game. We easily evaluate some stimuli and threats incorrectly, and therefore we sometimes react inappropriately. In fencing, the error of the first one often causes a different mistake on the other side. An exchange is then a series of mistakes where only a random hit or none occurs. 1

Trying to find a fixed point we can always rely on can lead to frustration and resignation to the study of fencing. Fencing is more often considered an art than a science. 2 Mastering it requires improvisation, invention, intuition, alertness, and wit. Thus, virtuosity in fencing is not based on the aesthetic principle 3 but on methods of finding solutions and in the variability of fencing itself. 4

In contrast to overly rigorous and scientific research, some people question the analytical examination of fencing at all. They think the success in it is based more on chance, physical conditions and deception. This is not the case, and simple statistics quickly disproves this statement (e.g. also from HEMA ratings) 5, which confirms that fencers consistently increase their chances of winning through training and experience. However, it is also true that in other, non-fencing sports, it is almost impossible to be, e.g. world champion defeated by “man from the street”. It can happen in fencing, and the probability is not entirely negligible. 6 The causes of this phenomenon would be worthy of separate analysis in a different article. I can see one reason why new fencers often see a disproportion in the amount of effort put into training and success in free sparing after a few years of practice. I would blame the way of training and overall fencing preparation. Fortunately, the methods of teaching HEMA fencing have undergone a significant change in the last decade. Paradigm shifts contribute to the fact that new learners catch up with older colleagues faster. Besides it slightly frustrates long-term fencers, it is a very positive phenomenon, which means that teaching methodology is improving.

For the success of fencing in itself, terminologically accurate concepts have no importance, and when a fencer has it in himself, it doesn’t matter if he knows the names belonging to the actions he has mastered. On the contrary, no one can do without clear definitions and terms during the teaching and coaching process. Simultaneously, uniting on common foundations contributes to a more accurate discussion over long distances, especially current digital days.

The meanings of terms in fencing have changed over time. I do not rule out that some names have been used differently in the past, or there will be a need to redefine or correct them later. Modern fencing terminology should be universal and its basic ideas identical to all weapons. It must not necessarily take into account all the historical nuances and exceptions of individual masters. On the other hand, the new terminology should make it possible to describe any historically faithful action.

Distance - measure

When we want to categorise different distances, we can look at tactical purpose or sets of actions doable from that particular group. The usual distinction between long and short can be additionally refined7 into 5 different groups. There are no exact measures in cm for each, and it depends on many factors. Although we have to start to learn distance handling statically, in reality, it’s a dynamic process that evaluates relations between the opponents, their positions and relative speeds.

-

Outside the measure - is a distance where neither the jump, step-lunge, nor the passing step is enough to hit the opponent. There is not much to talk about this distance. It is safest because even the fastest attack can be easily avoided by stepping back. Although at this distance, the movement of the opponent cannot yet be considered as [tempo] (#tempo), the tactic of combat begins here. All exercises with the first attack should be practised with an arrival from the outside the measure (zufechten).

-

Long distance - if I move closer and I am able to hit with a step-lunge or passing step. Now, I must pay attention to every movement, especially footwork. Another step or half-step can cause me big trouble if I am not doing it deliberately. The long-distance is still relatively safe. When I’m ready, my opponent needs a full passing step to reach me, giving me time to make him fall short. Though this is a reasonable distance to start an attack, if I start one on a prepared (static) opponent, my chances of a direct hit are still small. Without proper preparation, I would instead give the opponent an opportunity for a thoughtful counter-action. Compound attacks begin here.

-

Threshold distance or medium distance is somewhere between long and short one, and it may still seem like a long distance to an inexperienced opponent, but I can hit him in an inclined position when I move the body’s weight over the front foot sooner than my rear foot gets before the front one. It’s direct attack distance because the opponent does not feel imminently threatened yet, and the attack can be fast enough for the parry to come too late. But if I only start to think about the attack, it’s too late. You must have it already ready. 8

- Short distance - by moving forward from a medium distance, I get to the most dangerous fencing distance. Now my opponent and I can reach each other without stepping only by extending arms. It’s physically impossible to react in such time so short it takes to hit in this distance. 9. If I found myself in this distance and I have no well-prepared ongoing plan, it’s too late to anything. I got probably a hit already. In the short distance, proximity already complicates avoiding the bind (e.g. disengagement, coupe), but techniques such as Winden with cut or slices, Duplieren, etc. still well possible. Nobody should stay at this distance longer than necessary to finish the intended action. But prolonging the span to a long-distance or significantly shortening it is advisable. It is the riskiest distance with a high chance of double hits. If blades bind each other, they touch around the middle.

- Close distance (corps-a-corps) is when you approach the opponent even further. It’s no longer possible to attack from the bind only by using a blade. Blades meet there stong to strong (Stercke/Forte). I can easily touch the opponent with my hand, enter the wrestling, use punches, pommel strikes, crossguard teardowns, locks, hip-throws, etc.

Thanks to the various physical characteristics, it is clear that my opponent can already stand in the middle distance and hit me by tilting or extending his arms, and I will still need a step. The advantage of long arms and overall height is present in every combat sport. The only thing fencers are equal is the distance of the tip from the hand. This should be borne in mind by shorter swordsmen, as it will always take them longer to hit deep targets (i.e. torso, head) than their opponents, and therefore they should choose hands as a target more often to reduce their proportional handicap. At present, some fencers promote that the hand hits or snipes are inferior and less valuable than proper cuts and thrusts to the torso or head. However, anyone who has ever been injured in fingers or on the wrist can form own opinion on how effectively such an attack would be able to end the whole duel.

Offensive and defensive actions

Attack

Attack and thus Vorschlag (attaque) is an initial offensive action that would have the potential to injure an opponent if performed with a real weapon. The hand with the sword is being extended and approaches continuously to the open target. If the attack is performed from the correct distance, it is supported by the movement of the legs or body. An action in which the opponent steps into closer range, but his weapon does not accelerate towards the target (does not get hurting potential), or is just about to launch cut or thrust (the weapon is standing or retracting) is called preparation (préparation).

Simple attack follows just one goal, straight path, from the initial position until the actual hit. The most commonly used attacks with a long sword are the upper right cut or a direct thrust to the chest or head. These are the longest (in terms of range) and the fastest sword attacks. A properly executed simple attack can’t be changed to another one or cannot be revoked. 10

If I perform and attack in a way, my first action serves to lure my opponent’s parry. Then I change my final target to another opening (which is optimally provided by the defender himself). I have made compound attack. Actions that precede the final hit are not real attacks; we call them feints. For more details on compound attacks, see Fehler and Durchwechseln.

According to the initial position and chosen target, the term direct attack is used for an attack completed in the most direct and shortest possible trajectory. 11 Indirect attack first needs a movement that changes the weapon’s direction (e.g. to avoid the opponent’s blade), and only then it can reach the target. An indirect attack takes longer than a direct attack and gives the opponent an opportunity for a timely counterattack.

An example of a direct attack is the already the mentioned uppercut made from the preparatory position Vom Tag with a sword on the shoulder. An indirect attack is, for example, a cut on the forearm of the opponent’s right hand if we are standing in a left binding. The point first travels upwards along the opponent’s blade until it is free, and the binding no longer prevents the cut of his hand. (see Blade releases - oben abnehmen/coupé)

Before the attack itself, fencers often perform pre-signal moves. Some are intentional, others resulting from a technical error or a bad habit, like backswing for a cut or pulling a sword back. If it’s happening outside the measure, it’s more or less okay. Suppose I get into the medium distance during the backswing. If it is an unconscious mistake, the ready opponent can easily use it in his favour. On the contrary, if it is intended, my planned provocation gives the opponent a false sense of safety for an attack. Pre-signals in the body can be swaying of the knees, tilting, squeezing the handle harder. With such an action, fencers are preparing for faster, more vigorous, longer attacks, or again it is a provocation to get some opponent’s reaction.

An attack into the opponent’s preparatory phase is often a good time to surprise him relatively safely with my own attack on preparation. The attack on the preparation can be a cut, thrust, or slice. One among named longsword techniques, Ansetzen, is a technique where I hit an opponent in the early stages of his attack or when he only intends to launch his attack. Ansetzen hits with the point in line (Langort, or Ochs) during an opponent’s preparatory action, which may be a backswing or another signal. 12

To denote the attack on preparation when it is a cut or slice, we can use the term Nachraissen (in Vor). 13

Renewal of attack or a Nachschlag is the attacker’s continuation of the offensive after the first attack was covered or voided.

- Remise is a continuation with a direct offensive. For example, the vorschlag with uppercut falls short, and although it ends with the point in the line and does not reach the opponent. A remise is following direct thrust into the chest from the position where the uppercut has ended.

- Redoublement is an indirect or compound offensive action. For example, the attack with the upper right cut is parried, and the parry has made an opening on the opposite side. The attacker cuts around the head to the left (zwerch umbchlagen).

- Reprise is in the attack’s repetition after withdrawing back from the lunge or step of the first attack.

Counterattack

Counterattack is an offensive or offensive-defensive action performed during the opponent’s attack (simple and complex) as a response to his movement. The counterattack may or may not include a defensive portion. This defence can be an opposition with a weapon that prevents the opponent’s attack from effectively hitting or dodging, ducking the body.

Counterattack with opposition which deflects an attack and hits the opponent is represented in KdF, for example, by the principle of Absetzen (time thrust), or Zwerchhaw against the uppercut, Schiller or Zornhau ort (time cut).

On the other side, Ansetzen can be used as a counterattack to the early phase of the attack, or before the last action of a compound attack (stop-thrust). Schiller against Durchwechseln 14 or Langort Schiessen15 agains low pflugh thrust are another similar examples of the stop-thrust with longsword.

In this form of counterattack, the defence relies either on a stopping power of the point (Ansetzen vs Durchwechseln)/cut (Krumphau) or withdrawal from the reach/evasion (Überlauffen).

The term “attack” or “counterattack” alone says nothing about who acted right or wrong, who would be injured in a real fight or would get around without damage. Individual schools and fencing directions deal with these questions and have different views on them.

But we are here to understand the fencing tactics, and it is essential to learn how to distinguish between attack and counterattack. Sometimes the difference between an attack and a counterattack is subtle, and their initiation may seem almost simultaneous. It doesn’t matter if the attack starts 50 or 100 milliseconds earlier from a tactical perspective. To differentiate attacks from counterattacks, we watch for not only which weapon moved first but also for other signs like foot actions, preparatory actions, and weapon swings.

In a situation where two fencers start in a long distance, one fencer stands still, and the other one steps into the medium distance to hit. If both perform correct simultaneous offensive action, the attacker is the one who moves forward. The attacker initiates an exchange, and the other swordsman reacts because he would not reach the opponent himself but relies on the attacker to shorten the distance. Without an attack, his action would be pointless.

However, it does not mean that in a match where a double hit occurs, it is always the case that one has attacked, the other has counterattacked. A situation where both act independently and, therefore, both are in attack is not unique. Simultaneous attack is an action when opponents are at a long distance and simultaneously move forward with their attacks because they similarly evaluated the opportunity as suitable and the opponent’s movement conditioned neither action. The simultaneous attack is a phenomenon inherent in fencing, although it has never been desired and will never disappear. From a tactical point of view, this is the equal fault of both or none, which cannot be avoided in some situations. From a pedagogical perspective, this is a mistake more petite than a double hit in an exchange, where it is clear who made the attack and who just reacted. Regardless of perspective, both could be fatal in a “real-life duel”.

A committed Vorschlag is irrevocable, and therefore in the simultaneous attack, it is almost impossible to avert the double hit. As for the counterattack, the reacting fencer already had information about the ongoing threat, and therefore not only could but also had an obligation to choose appropriate defensive or offensive-defensive action to prevent double.

The term simultaneous attack can also be used even if both fencers erroneously remain statically in the middle distance or shorter distanced and both decide to attack. Steps are not required for an attack at such a close distance, and therefore both can start concurrently and without enough time to recognise or react to the opponent’s intentions. Observing an attacked first at such distance is difficult even with slow-motion footage.

Defense

A parry is a defensive action that is performed with a strong part (Stercke) of the blade (or crossbar) against a weak part (Schweche) of the opponent’s blade. The parry, whether static (functional only against cuts) or with a movement against the incoming attack, deflects or stops the attack. There is no attack (cut or thrust) during a parry, but this does not mean that the point cannot endanger the opponent.

Parries in the modern concept have not earned such a prominent place in texts as, e.g. positions (leger), many of which can also be used as them: Ochs, Pflugh, Krone, etc. Instead, the Lichtenawer system contains the concept Versetzen. And in several meanings. Sometimes it can be identified with the term parry [^ 8]. Elsewhere, depending on the context, it is a counterattack with the opposition, other times even an attack with a secured line against an opponent’s counterattack. Treatises tell us that Versetzen is done badly (by ignorant swordsmen) if the point aims upwards or to the sides 16. We can call it a parry in which the point does not immediately endanger the opponent. Proper Versetzen is either a counterattack with the opposition or a parry with an immediate retaliation, where the point constantly threatens the opponent.

In fencing with light weapons (foil, epee, sports sabre), parries and counterattacks have different efficiency than in fencing with a longsword. Although counterattacks are generally risky actions, they are even less reliable with weapons with extra light points and low momentum. With such, we prefer parries that can temporarily “disarm” the attacker and steal the pace for an early riposte. On the contrary, if we want to gain a similar attack-stopping effect with a longsword, more energy must be expended (see Krumphaw or Zornhaw). A parry that would be lightly placed in the path of the incoming cut might too weak to break the opponent’s Vor and provide time for a riposte.

Evasion is a defensive action of the body, where the swordsman prevents the hit by increasing the distance (breaking the measure) or otherwise changing the spatial position of the target to which the offensive action is aimed. Increasing the distance has a great advantage over other defensive actions because it gets the fencer out of reach, and thus it is a safer form of defence than any kind of parry. In fencing with a longsword, turns not used to the same extent as in fencing with one-handed weapons. Rotational voids like volta, inquartata, giratta, where I hit the opponent, and I get my body from the path of the opponent’s attack at the same time, cannot be used without releasing one hand from the handle of the sword.

Riposte is an offensive action taken immediately after a defensive action. As an attack, it can be simple or complex, direct or indirect.

Blades releases for indirect attacks

If my opponent’s blade prevents me (by touch, pressure, or just by spatial position) hit him by a direct attack, I must release my blade, bypass the opponent’s weapon, and touch the opening in different line.

If I sink the tip under the opponent’s blade and constantly aim at the opponent, it is disengagement, or Durchwechseln (cavatione, degagé). Durchwechseln can be performed as part of my own compound attack or as a reaction to an opponent’s attack on my blade, where I avoid the incoming cut, which then flies off the axis of fencing and allows me to hit the opponent when he can not defend effectively. Durchwechseln can be performed in both hanging positions. Either in Pflugh or Ochs.

Bypassing the opponent’s blade from above, Oben abnehmen, would be referred to in modern terminology as cutover (coupé). It is a movement along the opponent’s blade up to the tip and then back down with the cut to the target from the other side of the weapon.

Umbschlagen or cut around is a transition to an opening on the opposite side in an almost complete circle, often around the swordsman’s head. The most common is the horizontal Zwerch or the sloped Oberhau.

If my opponent, e.g. after the parry, falls on the weapon and pushes it down, neither Durchwechseln nor Abnehmen can be used 17. Umbschlagen would still be possible, but when I pull the sword back, the opponent can use this opening for a cut or a slice through my hands or forearms easily18. For such cases, Schnappen comes in handy to make your blade free. At first, I push the pommel forward over my opponent’s blade, and my sword hangs almost vertically down. Then, I hit and push the opponents’ hands or at least his blade with my pommel, thereby restricting his weapon’s movement. Finally, my blade flies around from behind my head and hits the opponent in the upper opening. If the action started with the opponent’s bind from the left, then my arms are cutting crossed. If I do Schnappen after a bind from right, I cross my arms at first and uncross them during the strike.

Tempo

The meaning of the word tempo fencing context is different from common Slovak usage. Besides, in fencing, it can also be understood in at least two meanings.

The first meaning is a term of a relative unit of time (tact/beat), in which it is possible to perform one indivisible fencing movement. E.g. thrust, lunge, parry, change of position, transfer of weight from the front leg to the another, etc. Depending on the nature of the action (and the fencer’s physical abilities or mental state), it is clear that different tempos may last for different periods of time. But there is not a single one precise value of how many milliseconds tempo should last. Thus, a compound attack may consist of two tempi/tacts, e.g. feint attack on the right and indirect attack to the left.

Example: a simple attack with a lunge is performed in one tempo, while a compound attack with a lunge is two-tempi, but the actual execution time of both actions can take a similarly long time.

In the second sense, we understand the word tempo as an opportune moment, a point in time (in the Greek philosophy of Kairos), when I have an optimal time to succeed with my strike. The tempo’s length is the time which the opponent gives me unintentionally (mistake) or intentionally (challenge, provocation) to perform my action. It is proportional to my chance of successfully hitting my opponent19. Whole fencing and every situation there is about tempo: to use it or lose it.

If an opponent has an opening, it’s a tempo for me. It is better to say if he will have it the very next moment because things usually don’t happen statically in fencing. Every situation has a record of past actions, which have to lead to the current snapshot of positions and momentums. Suppose the adversary has a longer trajectory to cover than me to finish the touch; it’s a tempo. Even if we both are standing still (by) at a long distance, the tempo is too short, and I won’t hit him in time. Because we are statical now, I would need to move towards him in the next moment, and he has another time for his reaction. On the contrary, it’s an ideal tempo if we are at a long distance again, but the opponent is already stepping forward and pulling the weapon back. He has just given me an opportunity, and he will have hard times reacting. Right moments are when the opponent moves in the attack, defence, or footwork. When using the tempo, we assume that the weapon/hand/body cannot perform two different actions simultaneously, i.e. a hand that moves forward at full speed cannot move back into the parry concurrently.

In Lichtenawer fencing, three terms Vor (before), Nach (after) and Indes (during, Intus, Interea) appear when talking about timing. The terms Indes and Nach are sometimes misunderstood nowadays, differently to the context of manuscripts. Vor consensually means to take the initiative in an attack and keep it. Nach was sometimes incorrectly considered as parrying and Indes as a counterattack. In my understanding, Nach is any activity that is performed in response to an opponent’s stimulus. Indes we could use as a twin to the term tempo.

I perform actions in Nach Indes, i.e. in ideal tempo, so that the opponent is in an unfavourable situation and cannot react in time or at all. For example, when he already has his attack launched and cannot stop it before my counterattack lands (absetzen, uberlauffen). If the counterattack was not in tempo or Indes and I am too early, the opponent would be able to change his action and avert the counterattack. If I am too late, he will occupy the space needed to form the opposition to prevent the hit. Using Indes in Nach gains to Vor by re-taking the initiative in response.

Indes can also be used with Vor to keep the initiative and prevent his opponent from taking his own actions or making a successful hit. Examples for longsword are compound actions like Durchweschseln or Fehler. 20

Tactics

Invitation (Chiamata) provides an opening by exaggerated parry or position (apparent tempo) to an opponent to provoke him to attack the target offered. The challenger must have the answer for potential attack prepared: counterattack, parry-riposte. The advantage of a well-executed challenge is that it reduces the range of actions to take into account and gives the opponent the feeling that he can hit freely.

Provocation has a similar goal to the invitation. Only the way of stimulation can be more diverse. Blade strike, stamping, exaggerated backswings or pulling the weapon.

False attack complements previous concepts with a fake attack, which does not intend to hit because it is too short, slow or otherwise imperfect. The attacker keeps a reserve in it to react to the opponent’s provoked response.

First intention

Attacks in the first intention or the first plan attacks are actions prepared in advance, and their final form is known to the attacker. We can include simple attacks but also compound attacks to this category. For example, a beat attack (beat to the blade with a subsequent attack on a target) or a premeditated Fehler. For both, I know my complete plan in advance. The feints where I choose my final hitting action (a trompement) according to the opponent’s reaction without having it ready are more than regularly unsuccessful in practice. We do not consider multiple feints to create an opening among the action of the first intention.

Simple attack

The attack is the basis of fencing, and without it, all other elements would not make sense. A simple attack performed correctly from an appropriate distance is an effective way to hit an opponent. Without unnecessary preparation, it is surprising and difficult to stop with a stop-hit. The disadvantage is that to hit with high chances; you have to approach the opponent dangerously into threshold distance

Parry-riposte

Defence in the first intention is a fully or partially prepared action, where I plan to react to the opponent’s attack and then hit with a riposte (simple and compound). I must not stand still21 waiting until the attacker brings me the cut or thrust according to my wish. Otherwise, I may never be able to cover the offensive without being hit. Although I am a defender in this situation, I have some means to influence the attack’s timing or direction. Invitations help me to reduce the potentially endangered target. If the opponent bets on a simple attack, he must always attack into parts not covered by my blade. E.g. blade covering the right lower opening makes my opponent attack right high or low. If my opponent is chasing me and I am retreating, a sudden stop or slow down encourages him to start with his attack. After a given stimulus to the opponent, I am ready to parry immediately without even waiting for the attack. Otherwise, I might be surprised by the attacker’s vorschlag.

Compound attack

An answer to the parry riposte 22 in the first intention is a compound attack. Feint is a compound offensive action that begins with a sham attack in order to lure the opponent into the parry and create an opening on the opposite side for the trompement. In the broadest sense, a feint is an action of the body to confuse the opponent and conceal my intentions. I strive to provoke a reaction that will allow me to get into a favourable distance and gain a tempo to complete the strike.

In the Lichtenawer teachings, we find two named categories of feints:

- The first is the offensive Durchwechseln or the already mentioned disengagement. The first phase of Durchwechseln is a false attack with cut or thrust but an actual indirect attack is always a thrust.

- If the first and final attack of a feint is a cut, we use the term Fehler. A typical example is an indicated uppercut to head suddenly stopped and redirected into the lower cut on the torso. Or directly, the false uppercut on the right finished into an uppercut to the left.

The third method is not explicitly mentioned in the texts, but it is also a common way of confusing an opponent. A fake direct thrust and the subsequent oben abnehmen/cutover above the opponent’s blade on the hand or head.

Compound attacks by cutovers or Fehlers are more difficult to cover than Durchweseln feints. The cut parries require a better and stronger cover taking more time. On the contrary, both of these compound attacks that end in a cut are more vulnerable to counterattacks.

Counterattack

The last of the first intention repertoire is a counterattack. The goal is to anticipate the moment when the opponent pulls off his attack or, better to provoke him to do that by smart distance handling and footwork. Then, I can surprise him with a well-timed counterattack. This tactic is usually successful against long attacks or attacks with long preparation when we can read easily the opponent’s intention to attack. Or when the opponent misjudges the distance and found himself in the medium distance (which is too close for a compound attack), he still chose a compound attack22 when he had been already attacking. I have a choice of actions already described: stop-hits, attack on preparation, time-thrusts/cuts.

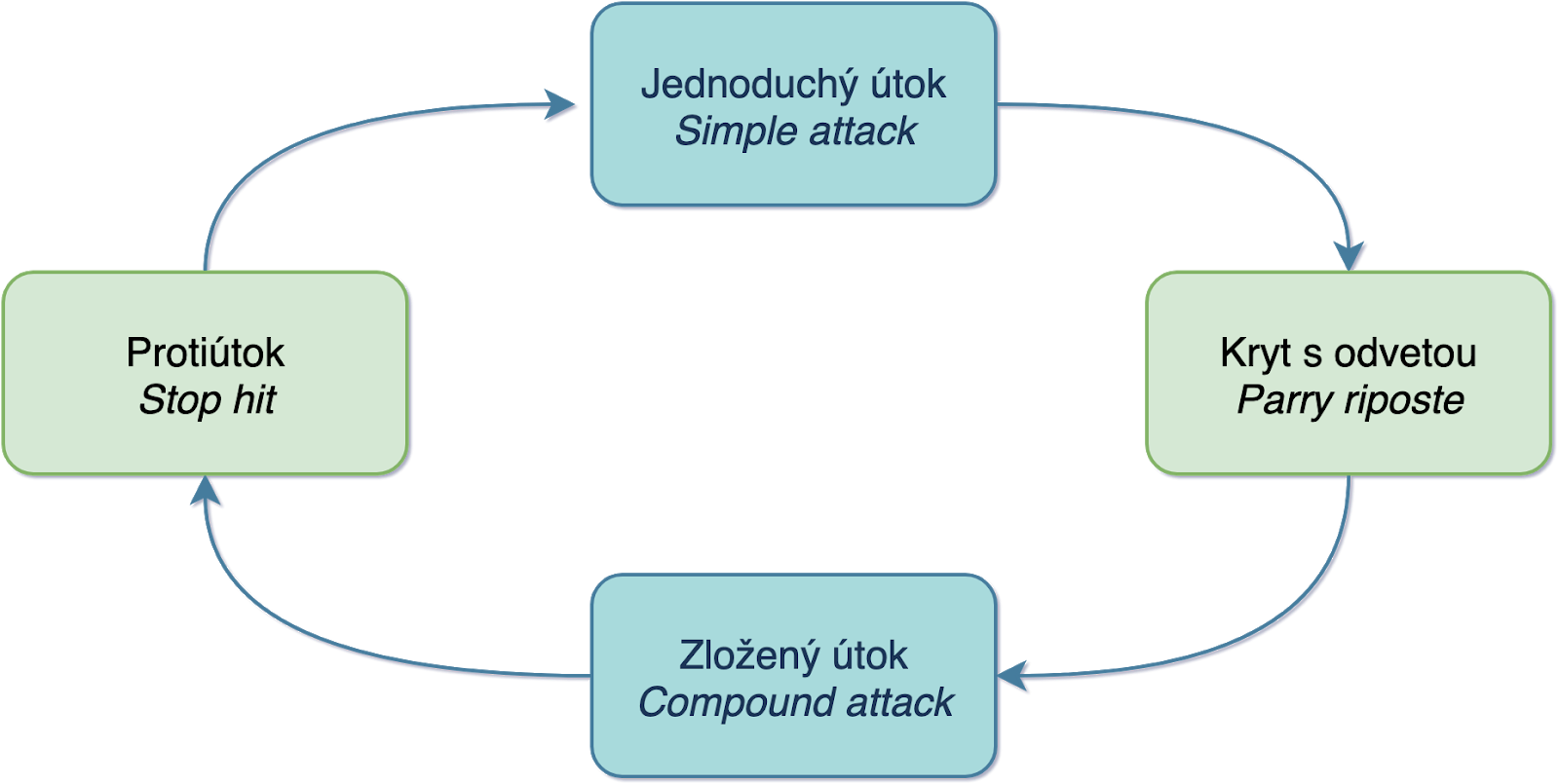

Tactical wheel

When we put the first intention’s actions into a graph and connect vertices with oriented edges, we get the so-called tactical wheel. Arrows show which action can be an excellent tactical response to a particular tactic chosen by your opponent. A parry-riposte breaks a simple attack. If I know that the opponent will strive for parry-riposte, I will carry out a compound attack instead of a simple one. If the opponent often makes compound attacks, long preparations, or attacks on the legs, I can stop him with a well-timed counterattack.

Image #1: First intention

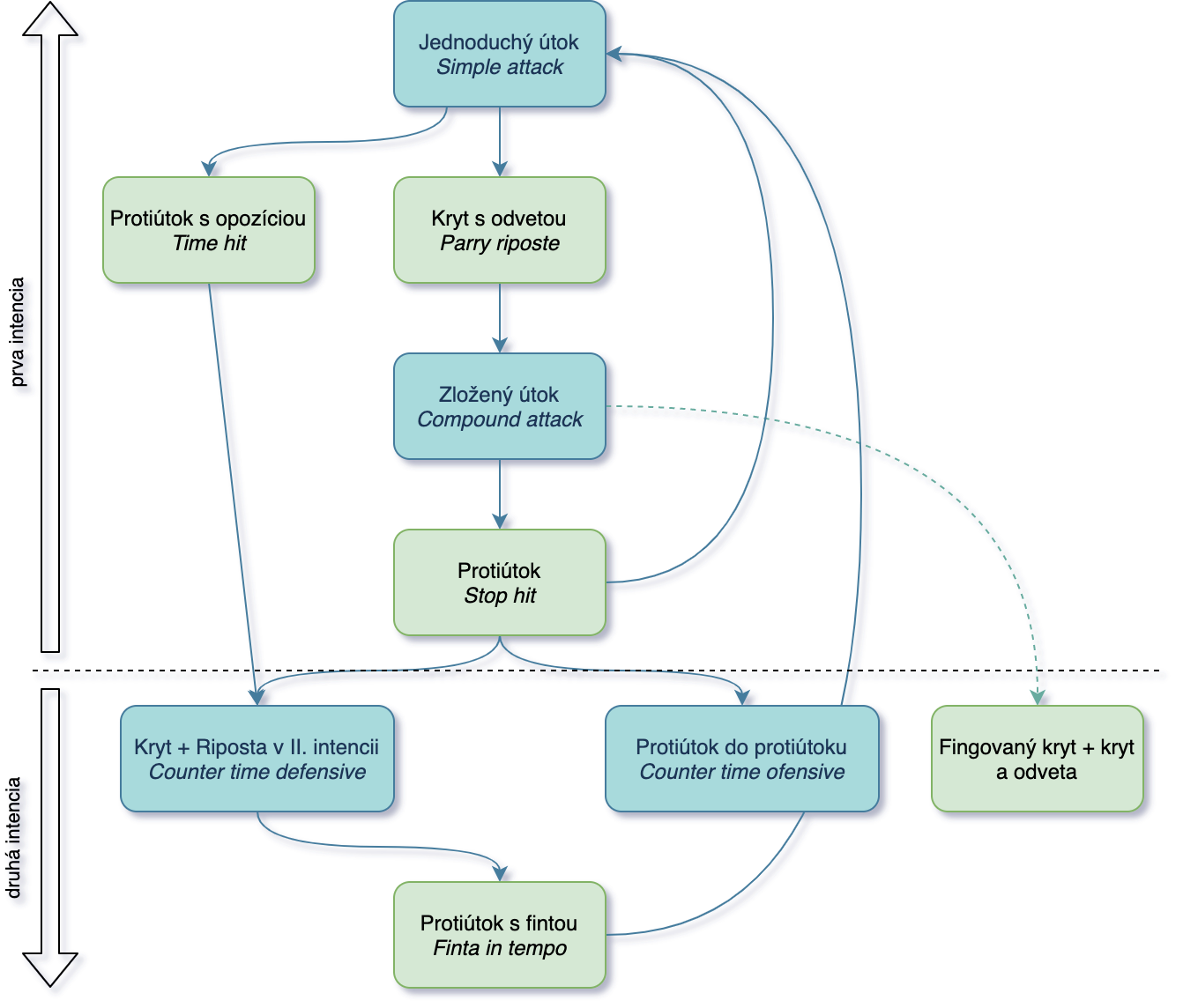

Second Intent Actions

First intention fencing is a natural, effective, but often naive approach. More experienced swordsmen think one step further, and the actions of the first intention are no longer enough to “overwhelm” the opponent. The answer is the tactically more complex actions of the second intention.

To hit in the second intention, I need the initial movement, e.g. a false attack that provokes an opponent to act expectedly. Then I can apply my intended winning strategy.

The first tactic is second intention parry-riposte (defensive counter time) or counterattack in second intention (offensive counter time). I have to manipulate the opponent to a counterattack by giving him a false tempo he evaluates as a safe opportunity. To that, I can use the tempo of the foot; when I initiate a step without preceding threat with the weapon. Or I may swing back for a fake cut in the threshold distance. If the opponent accepts the slow starting attack or footwork signals saying I am about to launch an attack, he makes a mistake. I am already waiting for his, e.g. a direct thrust to my chest. Unlike an actual attack, I can stop, parry opponents stop-hit and riposte with my point. In contrast to first intention parry-riposte, I control the conditions here to a great extent. If I’m just waiting for an attack, I can be surprised by the timing and direction. I can manipulate the opponent when and where to attack with my fake attack instead 23. Alternatively, I can decide on a counterattack instead of the parry. For example, I redirect my initial attack into Krumphaw, which hits the counterattacking opponent’s hands. I remind you that it is critical to determine the right amount of your provocation. If I put into it with great energy, then I might not be able to cope with a well-timed counterattack. On the contrary, if my false attack is just subtle, the opponent can completely ignore or overlook it.

If I notice that the opponent often relies on attacks with a secondary intention, I may move further with my tactical intention. I know that the answer to parry-riposte should be a feint or compound attack from the first layer of tactical wheel sequence. In the second intention, this is called feint to tempo (feint in time, finta in tempo, feint counterattack). So if I suspect that my opponent is looking for my counterattack with his fake attack so that he can defeat me with a second intention parry-riposte, then I will not be tempted by a direct stop-hit. Instead, I’ll just feint the counterattack and finish it to another opening. The opponent will get hit while searching for my blade.

The last remaining move on the tactics and counter-tactics chart remains an action that beats the finta in tempo. What is the best against composed attacks? Don’t give them space and time. If the opponent tries to fool me with a feinted counterattack, I should finish my initial false attack. From the viewer’s point of view, it will appear that I performed a simple direct attack, which may have had a slower beginning. And by completing it, I will steal the opponent’s time for his trick.

The aforementioned tactical sequence is not a decision algorithm I can simply apply during exchanges. That is not possible. I should have my tactic ready before the very start of the exchange. It has to based on observing the opponent’s reactions. Some types of opponents like to parry more, and others just counter all the time. If I fail my intention of a simple attack in the first attempt, it is not immediately necessary to switch to a compound attack. (Or generally, at any point of the tactical diagram to go one step further). I might have failed with ideal preparation for my strike. A faster, more unexpected, or more fierce attack can score.

In addition, a tactical diagram can also be a tool for training lessons. If I master a technique like a drill in the first intention, I might try the same piece in the second intention situation. There I can dictate better conditions when and how I perform the action. Therefore I will get closer to the sparring reality.

Image #2: Rozšírený taktický diagram

Conclusion

Knowledge of fencing concepts alone will not make anyone a better fencer. It may even seem like a purely theoretical absurdity, detached from reality. I acknowledge that such a phenomenon is not uncommon among the martial arts, and some schools or styles are closed in their own bubble, from which we can no longer see what is still meaningful and what only useful in their ivory towers. But for progression in modern HEMA, we need to tame the chaos we observe when watching free plays. We need to categorize, analyze those concepts. Until we start using different names for different events, our brain cannot even create a distinct pattern for solving a given situation. Therefore, it cannot distinguish the signals for it, and the solution will be somewhat random. Not systematic. It does not mean that we will always be wrong, but the outcome will be uncertain, based more on intuition or luck. And that’s not enough beyond a certain level of proficiency of a swordsman!

-

An unexpected or confusing action can frighten an opponent enough to stop, withdraw, or redirect their attack against an opponent’s weapon. ↩︎

-

Although the word science - scienza is often used in Italian writings with the rise of the Renaissance and formalization ↩︎

-

See leychmasters teachings in the anonymous Hs. 3227a in articles about nice and wide fencing. The aesthetics of fencing is not given by external requirements for the beauty of movement but rather in motions’ efficiency and skill. Therefore, without a more profound knowledge of fencing, it isn’t easy to recognize it. For the layman’s eye, fencing is almost always just theatre. ↩︎

-

Although fencing contains several always valid principles both in the past and today, it is also subject to “fashion” trends. If one element becomes more dominant in tournaments than others, it will quickly expand into many fencers’ repertoire. Over time, however, it “shuffles” again, and most competitive fencers become immune to it, which gives a chance for a new (but recycled) unconventional piece to be soon popular. And so on in cycles. ↩︎

-

The higher the swordsman’s rank difference, the greater the chance that the better-ranked will win regardless of the rules of the tournament http://swordstem.com/2018/08/15/hema-ratings-does-it-actually-mean-anything ↩︎

-

And even more so for sharp duels. Often older authors who experienced this era mention that many experienced swordsmen were injured and defeated by technically inferior swordsmen. Nagy Krisztina: Felső-Eöry Cseresnyés Zoltán, 1901: Nonthreatening outcome of the sword-duel, and its possibilities or Aldo Nadi, 1943: On Fencing ↩︎

-

Or six groups. A. Kohutovič: On Efficiency and Safety, Proceedings of Tyrnhaw 2012 ↩︎

-

A. Kohutovič: Vorschlag, Proceedings of Tyrnhaw 2011 ↩︎

-

SRT - simple reaction time. Respond to a simple stimulus without choosing an answer. For a visual signal, the median is around 210ms. ↩︎

-

Try to cut PET bottles with a sharp blade to verify. Ask a colleague to randomly shout a stop after you have initiated the cut to the target, whether you will be able to stop the cut or, conversely, whether you will not spoil even those attempts that should cut the target without slowing down in anticipation of the change. ↩︎

-

Cod. Hs. 3227a: “[13v] Vnd dy selbe kunst ist ernst gancz vnd rechtvertik / | Vnd get of das aller nehest vnd korsrtste / slecht vnd gerade czu / | Recht zam wen eyn ° eyne ~ hawe ~ ader stechen welde / | man im deñe eyne ~ vadem ader snure an seyne ~ ort ader sneyde des sw ° tes bünde / | vnd leytet aber czöge | dem selben ort ader sneide off ienes blössen / | den her hawe ~ ader stechen selde / | noch dem aller nehesten / · Kortzsten · vnd endlichsten ” ↩︎

-

MS Dresd.C.487: “[36v] wen er dir oben jn will hawen So merck die wil er dz schwert vff zů dem zlag so rayse im nach mitt dem hawe oder mit minem aich stich vnd triff in zů dem / obern blöß ee eritt dem haw wider kump oder fall im mitt der langen scheniden oben in sin arm vnd truck in domitt von dir ” ↩︎

-

Nachraissen* means to travel after or to follow after. In Vor, I follow my opponent’s preparation and use it as a moment for my attack. ↩︎

-

Hs. 3227a: “[28v] Vnd wer mit durchwechsel drewt dere wirt mit dem schilhaw beschemet / vnd eyner sal wol schilhawen vnd lank genuk vnd den ort vaste schiessen anders her wirt gehindert mit durchwechsel / vnd eyner sal wol schiln mit dem orte” ↩︎

-

Cod. 44 A 8: “[23v] wenn dw gegen ÿm stest | vnd beheldest dein swert an deiner resel achsel stet er denn gegen dir in der hu ° t des phluegs | vnd wir dir vnden zu ° stechen | So haw In mit dem schilär lanck oben ein | vnd scheuss Im den lanck ein zu ° der prust | So mag er dich mit dem stich vnden nichl erlangen ” ↩︎

-

Ms. Germ. Quart 2020: “Das ist das dů nicht versetzen solt als die gemeinen vechter thůn Wann sie vorsetzn so haltenn sie irn ort in die hohe oder aůf ein seitn Vnnd das ist zůuersten das sie in der versatzůng mit dem ort nit wissen zůsuchn” ↩︎

-

We assume a short distance. ↩︎

-

Or pushing on the forearm Hendtrucken ↩︎

-

The tempo, therefore, depends on several variables such as the distance of my weapon from the target, the attacker’s need to take a step, the defender’s ability to stop his action, from the position and momentum of the weapon. In short, the time (preparation, lunge, attack) it will take me to hit the target must be shorter than the sum of the action times that the opponent must take to avoid the hit (stopping his own movement, parry or evasion). ↩︎

-

MI 29: - “Item wan du Ee kumpst mit dem hauw oder sunst daz er dir versetzen muß, so erbeytt Indes behende glich fur dich mit dem schwertt oder sunst mit andern stuecken und loß In furter zue keyner arbeytt kumen“, Unlike the modern tempo, the word Indes is not used for the moment for the initial attack itself. ↩︎

-

Wer nach get hawen [10v]…Glosa / das ist wenn du mit dem zů vechten zů im kumpst / So soltu nicht still sten / vnd auff sein haw sehen noch warten was er gegen dir vicht / Wist das alle vechter dye do sehen / vnd warten auff eins anderen häw / vnd wollen anders nicht thuen wenn vor seczen die bedürffen sich solicher kunst gar wenig fräwen / wenn sy ist vernicht / vnd werden do pey geslagen ↩︎

-

Durchwechseln is against swordsmen who like to cover. Cod. 44 A 8: “[31r] Merck der durchwechsel ist vil / vnd manigerlay / Die soltu treiben gegen den vechternn / die do geren vorseczen / vnd die do hawen / zw dem swert / vnd nicht zw den plssss des leibs” ↩︎ ↩︎

-

According to the direction of my attack or preparation. ↩︎