Schiller

AI Translation

In the next installment of this occasional series, I would like to offer you an alternative version of the Schilhaw against the long point or similar middle positions. Later, I will also discuss Schiller against Oberhaw, as both variants should interpretively converge.

Schiller Against the High Cut

Wan du mit dem zu vechten zu dem mann kümpst so setz din lincken fus vor vnd halt din schwert an diner rechten [25v] achseln Haut er dir dann von oben zu dem kopff so verwind din schwertt vnd spring zu mit dem rechten fus vnd haulb gegen sinen haulb mit der kurtzen schnden lang vß gestrackten armen oben vber sin schwertt zu dem gesicht oder brust… MS M.I.29, 25r

When you approach the opponent, stand with your left foot forward and hold your sword on your right shoulder. If he strikes you from above to your head, twist your sword and step with your right foot and strike against his cut with the short edge with extended arms from above over his sword to the face or chest.

Schiller Against the Plow and Lower Thrust

Wann dů gegenn im steest vnnd beheldest dein schwert ann deiner rechtn achseln steet er dan gegenn dir in der hůt des pflůgs vnd wil dir vndn zůstechn so haů in mit dem schiller lanck oben ein vnd scheůs im den ort langk ein zů der prust so mag er dich vnndn mit dem stich nit er langenn. Ms. Germ. Quart 2020, 74r

If you stand against the opponent and hold your sword on your right shoulder and he stands against you in the plow guard and wants to thrust you from below, strike down from above with a long Schiller and shoot the point long into his chest so that he cannot reach you with the thrust from below.

Schiller Against the Long Point

dz ist eyn stueck wider den langen ortt mit eynem betryegniß des gesichtz daß tribe also wan du mit dem zu vechten zu dem man kümpst stet er dan vnd helt dinem ortt gegen dinem gesichtt oder brust so halt din schwertt an der rechten achselln vnd schil mit dem gesichtt zu dem ortt vnd thun als du ym dar zu haulben wollest vnd haulb starck vß dem schiller mit der kurtzen schniden an sin schwertt vnd schieß im den ortt do mit lanck in zu dem hals mit eynen zu tritt dines rechten fus MS M.I.29, 26v

This is a piece against the long point involving a face deception, performed as follows: when you approach the opponent and he holds his point against your face or chest, hold your sword at your right shoulder and glance at the point, feigning a strike at it, but strike strongly with the short edge in a Schiller onto his sword and shoot the point long into his throat with a step of your right foot.

Langort and Middle Positions

Historical sources mention that Schiller is a good aid in situations where the opponent stands with arms extended, point towards my chest or face, i.e., in the Langort position. Schiller offers a simpler variant (so much so that it could be used in today’s tournaments) targeting the opponent’s hands. The second solution is more challenging and strikes the opponent in the chest, neck, or face.

A precise description of the Langort position will be hard to find in early manuals. The opponent is to hold the blade with the point towards my face or chest. In Hs. 3227a, the long point is oddly mentioned in the fourth position Vom Tag, but it’s hard to find any correlation with the later interpretation of this position. Other glossators mention Langort primarily in the Sprechfenster chapter. In this position, I wait and react in Nach to the opponent’s actions. The position itself, like other positions, is not an end but forms the basis of the Sprechfenster principle, which is neither a technique nor a position but a strategy.

Mörck, ee wenn du mitt dem zůfechen zů nahent an jn kümst, So secze dinen lincken fůß vor vnd halt jm den ort auß gerächten [123r] armen lang gegen dem gesicht oder der brust. Hawt er denn dir oben nider zů dem kopffe So wind mitt dem schwert gegen sinen haw vnd stich im zů dem gesicht. Oder hawt er von oben nider oder von vnden auff dir zů dem schwert vnd will dier den ort wegk schlachen So wechsel durch vnd stich im zů der anderen sytten zů der blöß. Oder trifft er dir mitt dem haw dz schwert mitt störcke so lauß din schwert vmb schnappen. So triffest du in zů dem kopff. Laufft er dir ein So tryb die ringen oder den schnitt.

Image #1: For illustration of the Langort position, I use an image from Joachim Meyer 1570, illustration A.

In the middle position or Langort, if the opponent has fully or nearly fully extended arms, it is quite difficult to find an opening. No part of the body offers a target for a direct attack. The opponent keeps me at a proper distance, and his targets, except for the hands, are far away. Another advantage is that the blade in a straight line is harder to bind than when it is at an angle and provides its weak part for binding. In attempting to bind, the opponent in Langort easily slips through with Durchwechseln and can attack into my tempo.

Langort, of course, has its disadvantages. Unlike the opponent in Langort, I know his reach. He cannot increase his reach from extended arms except by moving his entire body, i.e., by stepping. Additionally, the speed at which he can deliver a thrust is limited by the speed of his legs, which, as we know, are at least twice as slow as the hands.

Schillhaw also breaks the Plow position, or most middle positions, i.e., positions lower than Langort but with the point aimed at the chest or head. However, according to our experience, caution is advised against two variations of this position.

Against a static right plow, Schiller from the left seems too risky, as it is almost impossible to cover the opponent’s sword, which is far and at an angle. Against a withdrawn right plow (i.e., where the opponent pulls the handle towards his rear leg’s hip), I would prefer the analogy of Schiller from the left side.

Equally risky is striking Schiller against the middle position if the point is lowered to a lower target or creates a line at waist level. In such a situation, it is almost impossible to prevent Durchwechseln or a thrust to the hands with Schiller. Again, from experience, I advise avoiding Schiller and choosing completely different approaches, e.g., moving to scare the opponent, who in reaction slightly raises his point, allowing a bind or even a straight Schiller.

“Old” Version

The classic (or our previous) interpretation of Schiller, as shown in video sequence 9 and 10, is not entirely wrong but has its disadvantages. Firstly, it is very similar in principle to Zornhaw Ort, i.e., it tries to knock the opponent’s point off the line and then thrust into the vacated space. The main difference compared to Zornhaw in such performance is that it strikes with the short edge, which allows, unlike Zornhaw, to remain stable in the center even against static positions that offer no resistance. What I consider the main disadvantage of such execution is the dependency on the opponent and the way he holds his weapon. If the opponent is soft, you need to strike such a Schiller gently more to the center; if he is firm, you need to direct the strike more to the side and add force. This results in significantly variable success in hitting with Schiller, as such performance requires some form of feeling, or estimating the opponent before actual blade contact. If I estimate the opponent to be softer and he is actually hard, I will not win the center, and I actually give the opponent a tempo to assert himself. Conversely, if I anticipate greater resistance and adjust the strike accordingly, I will overshoot the point too far to the left, missing the opponent, making it difficult to return and hit. From such a state, I concluded that this dependency on good opponent estimation is not acceptable for consistent Schiller performance.

I know purists will claim that feeling is fundamental in fencing, but I dare to disagree. Feeling is perhaps the last resort on which I should base my fencing plan. The reason is simple: if it comes to blade contact, it is usually too late. Therefore, I must do everything to create a relatively safe plan before initiating the first attack. In this plan, I ideally account for the maximum possible restriction of the opponent’s reactions. For example, an attack on a completely stationary and prepared opponent has no chance of success. Such an opponent can choose from a vast array of reactions, which poses a great and unknown risk to me as the attacker. Therefore, I argue that breaking static positions (e.g., Zwerch against high Vom Tag or on the shoulder) simply does not work against at least minimally competent opponents. Every such attempt must be preceded by a “game” in which I force the opponent to move, even minimally, ensuring that when I begin executing my plan, he cooperates, albeit against his will.

Video Schilhaw - New Concept

Modernized Version

Perfect Line

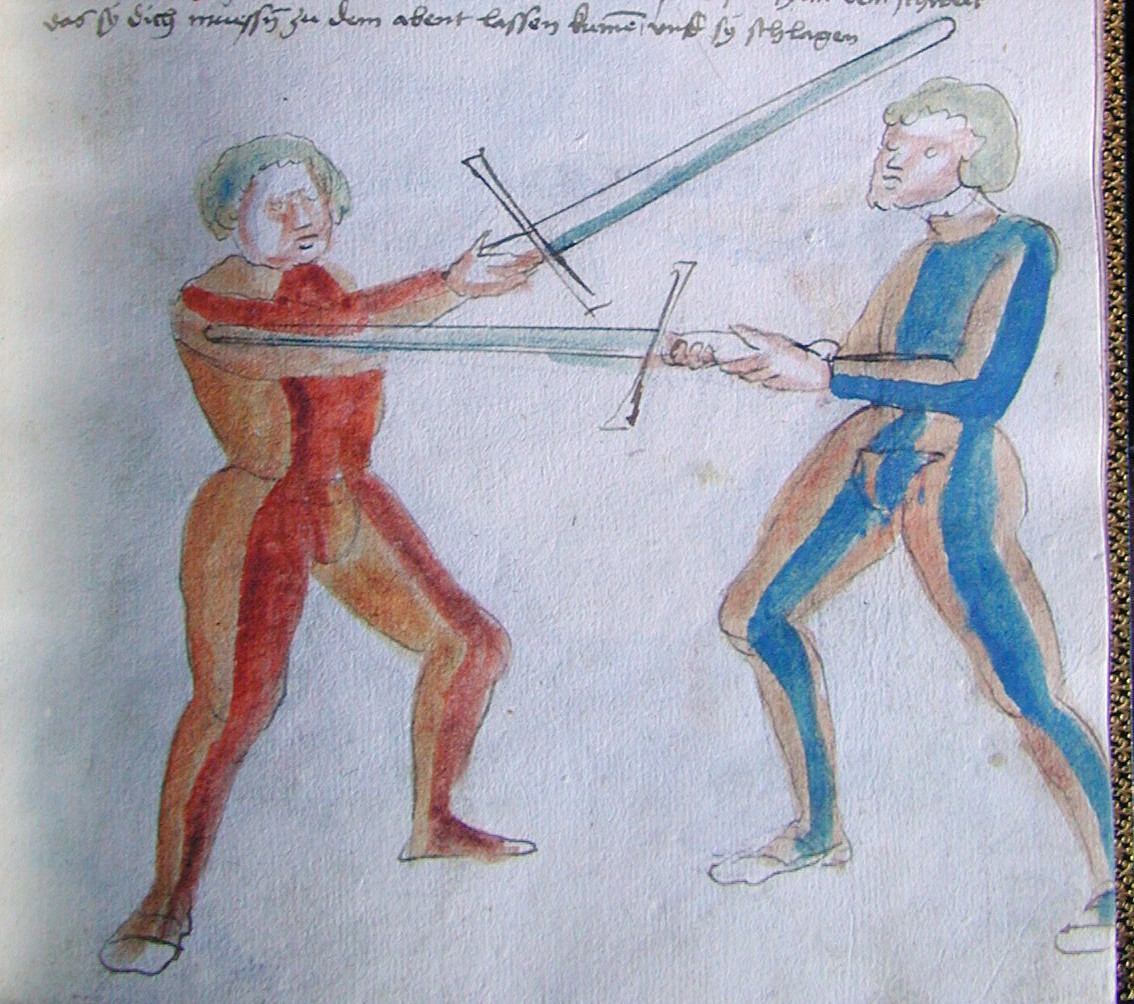

The first necessary condition for improving the performance of Schiller is the perfect line of the sword. Schiller breaks Langort but draws from this position itself. Unlike Zornhaw, in Schiller, both arms are fully extended to the maximum position. (See the image Ms. Germ. Quart 2020 or “So haw In mit dem schilär lanck oben ein / vnd scheuss Im den ort lanck ein zů der prust”). In Zornhaw, such a position is a mistake because full extension weakens resistance to the opponent’s pressure/force. However, this drawback only appears in a strike with the long edge. In the case of Schiller, it is a strike with the shortedge, and therefore this drawback does not manifest.

Our newer version does not rely on the power of the strike but on a stronger position that can more consistently win the central line. The desired final position of Schiller can be seen in sequence 7, where it is illustratively shown that I stand turned to the opponent as much as possible with my right side. The more I get my right shoulder forward, the greater the reach I gain. The left shoulder, on the other hand, is pulled back. The correct rotation reminds me of drawing a bow with the left hand, although I have no knowledge of archery. For comparison of different positions, I start in the video with Langort with the edge up and transition to Langort with the short edge, which remains sufficiently strong even when extending the reach by a few more centimeters. The pelvis remains oriented forward and forms an opposition to the turned chest. In the final position, my entire body is covered by the sword, and any thrust from the opponent must necessarily go outside. In some sequences, our hands bend to the side, but this is caused by the impact into the opponent’s body and the bending of the blade.

Trajectory

Unlike the mainstream version, I lead Schiller significantly more vertically and not diagonally. I can lead it almost vertically down because I am not trying to hit the opponent’s blade at all and knock his sword away. I lead the strike parallel to the line (slightly to the right) of the opponent’s Langort and focus on hitting the opponent with the point in the area behind his hands. I try not to focus on the opponent’s blade at all. Regardless of whether the opponent holds his blade there or pulls it away, I strike exactly the same. (This is easy to say but harder to do. For practice purposes, the opponent should try to pull the blade completely away to see if it affects the trajectory of my strike.) At the moment when I hit with the point, the opponent’s weak part of the blade is taken over by my strong part and the crossguard, so he cannot easily push my point away. Positionally, I push his point off-center, as seen in sequence 8 of the video. The bind occurs quite late, so I do not give the opponent a signal to react, as was the case in the original version. For this reason, I must not slide the strike along the opponent’s blade, so as not to give the opponent an early signal that he could immediately utilize to thwart my attack.

The way I strike must not be influenced by the state of the opponent’s Langort. The performance is exactly the same, whether he is strong or weak on the blade. Unlike the version where I try to knock the opponent off-center, here I am merely occupying the line with my Langort and do not rely on the power of the strike, so it doesn’t matter to me if he is strong or weak. Under no circumstances do I need to compensate for the trajectory of my strike.

Image #2: Schiller Cl. 23842 Cluny

Mechanics

In performing Schiller, I use a very similar rotational mechanic as I introduced in the Zornhaw Ort, but also in a separate practice video. (This can best be seen in sequence 21.) Although breaking a position does not require as much force as breaking a strike, proper rotational engagement certainly supports correct movements. Some colleagues from the fencing club criticize that my point lags behind the hilt in Schiller. This is true, but in the initial impulse when I start twisting the blade on the shoulder, I pull my hands to the level of the opponent’s point, thereby shielding myself against potential counterattacks. As I mentioned, if the opponent stands in full Langort, we cannot expect any sudden thrusts from him. The situation is different if he holds his hands lower and closer to the body. Then I also try to lower my hands in the first phase to avoid an unwanted thrust/stab to the hands. If the opponent stands with his hands relatively low and the point aimed upward, then I must also adjust the target area. I cannot afford to attack the head or neck, as I would not be able to control the opponent’s point, and it would be very easy for a double hit to occur.

If I strike Schiller against a position or thrust, I usually have the sword prepared on the shoulder in the standard position, i.e., with the short edge back (sequence 27). I rest my thumb on the shield significantly closer to the short edge of the blade, not in the center. This grip allows me to press the blade with my thumb, causing the short edge to shoot forward, enabling a direct strike. When performing Schiller against a strike, I am often not such a show-off, and I have Schiller prepared on the shoulder so that I can strike directly with the short edge without twisting the blade. The twist, which helps me clear the center more easily against a thrust, also gives me more power against a strike but at the cost of precision and adds a slight latency, which is why I often cowardly choose a simpler variant. I strike directly with the short edge without twisting. Not all sources mention this twist, and I think it is not necessary for the technique. Initially (circa 2003-2005), we performed this twist during the clash with the opponent’s blade, but this did not prove to be a viable path in the long run.

As for the step with the right foot, I may disappoint die-hard Meyerists, but I step straight forward when performing Schiller against the long point. I step diagonally only if the opponent is offensive. Then I start moving my center of gravity forward, hitting, and stepping only if the situation requires it. How diagonally I step depends on the distance from the opponent; the closer the opponent comes with his attack, the more I step to the side. A premature step to the side would pull my sword off the central line, completely ruining the technique. I would lose the advantage on the blade and also the reach, which is a crucial factor for the success of Schiller.

Alternative to Absetzen

In the associated video, there are versions against lower and higher positions. In some cases, when the opponent is too short, I can directly strike the head without needing to thrust. In principle, I can use Schiller against any middle position and thrust from it. It forms a kind of twin to Absetzen, which I can comfortably perform only if I stand in some middle position myself. Instead, I throw Schiller just like Absetzen against thrusts, only starting from a higher position (point up in the ready position).

Schiller is not a problem to start even in tempo vor, given its large reach. If a bind occurs, the position allows me to immediately continue with a strike around to the opponent’s upper right opening.

Strike to the Hands

“Glosa / Merck dass ist ein ander pruch / wenn er gegen dir stet in dem langen ort / So schil ym mit dem gesicht zw dem haubt / vnd thůe als du in dar auff wöllest sla schlachen / vnd slach in auß dem schilhaw mit dem ort auff sein hend”

A version of Schiller that we did not capture in the video and will not address yet is the direct attack to the hands. Such a Schiller is mentioned in one treatise against Langort, in another also against the high cut. Against Langort, it is a straightforward interpretation. Just to remind, in the following image, you can clearly see how Schiller passes through the maximum Langort.

Image #3: Schiller to the hands

In the version against the cut, I aim the point at the opponent’s hands before his cut can arrive.

Image #4: Schiller to the hands against a cut

Durchwechseln versus Schiller

The video does not cover another topic clearly related to Schiller, namely Durchwechseln. I would like to return to this topic sometime in the future, maybe even with a video on Durchwechseln itself. The oldest source, HS. 3227A, addresses the topic more generally but captures the essence that anyone who fences shortly with Durchwechseln will be shamed by Schiller.

Vnd wer mit durchwechsel drewt dere wirt mit dem schilhaw beschemet / vnd eyner sal wol schilhawen vnd lank genuk vnd den ort vaste schiessen anders her wirt gehindert mit durchwechsel / vnd eyner sal wol schiln mit dem orte / czu dem halse kunlich ane vorchte

Durchwechseln, or feints, in terms of modern fencing are compound attacks, i.e., consisting of at least two actions. Every such attack includes interrupting the first attack to avoid the opponent’s parry. Schiller fits precisely into this moment when the opponent is shortened. In the tactical wheel, we would say it is a counterattack to a compound attack. Schiller, with its reach, hits the opponent at the moment when he shortens his initial attack. Here the importance of a perfect Langort line is shown. No matter how much I strike Schiller to the side or in two tempos, I would never be able to catch the opponent’s “cavation.” Only maximum reach can break a well-executed compound attack from the opponent.

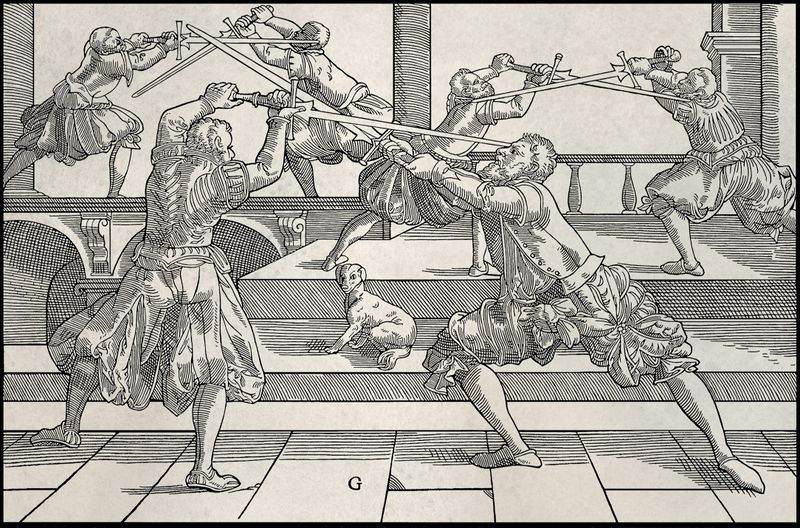

The image that might most closely illustrate Schiller as a counterattack to tempo isthe one from E.1939.65.341, where the right fencer enters into some compound attack of the left fencer, who fails to complete his second attack as he shortens his first attack, losing the Vor (initiative). (However, the image could also depict something entirely different.)

Image #5: Schiller against Durchwechseln

Against the Cut

My ideal Schiller should mechanically function the same against a position, thrust, or cut. However, it is not easy to use the same movement against various attacks, because although it is a similar strike, when performing against Oberhaw, I must focus more on other details that did not seem as important against static positions. I need to significantly enhance the forward movement of the pelvis and rotation to ensure my sword has the maximum momentum. At the same time, I must not focus on knocking down the opponent’s cut, as this would lead to a two-tempo action of parry and riposte.

Image #6: Schiller against a cut

One of the things that pays off the most is the effort to extend the arms as far forward as possible before the clash of blades. The farther away from me the impact occurs, the easier it is to cover even very strong cuts. At the moment of blade contact, my arms are extended (or ausgerackten = stretched out) and, since it is in the short edge position, they are at their strongest. If, at that moment, my arms were still extending, it might happen that the opponent’s blade breaks through and hits me with his cut. Very briefly, you can see Schiller against Oberhaw in the video from sequence 33. I realize that it is not very visible in the footage, but the stronger the opponent strikes, the stronger he himself receives. This holds true if he strikes powerfully intending to cut through. If he strikes powerfully but his goal is pressure, then his blade should slide into the crossguard, neutralizing his attack. (This variant is not in the video.)

The usual point of impact is the top of the head, ideally the seam of the mask’s covering cap. In the case of poorer performance or a stronger opponent’s cut, I hit at least the left shoulder. Perhaps this is why Ringeck advises attacking the right shoulder, because if the clash of blades slightly shifts the trajectory of the cut, you hit the head, or at worst, the left shoulder.

Cutting Schiller in two tempos on the opponent’s weak blade and then rotating as a riposte to the head does not appeal to me traditionally. I do not find a hint of a two-tempo performance in the early writings, and it contradicts the notion that Schiller should use its reach to break through Durchwechseln.

Discrepancies with Treatises

This new interpretation also contains discrepancies with some texts. For example, the Dresden Ringeck mentions an attack with Schiller on the weak blade, which is quite close to the point. I see a problem in this with the given interpretation. In our new interpretation, the blade strikes more in the center rather than on the opponent’s weak blade. If I wanted to strike the weak blade, I would have to alter the trajectory of the cut more to the side, and I could not stay in the center. Such a procedure did not appeal to me because it is extremely short and increases the chance of the opponent’s Durchwechseln. Although Schiller should break Durchwechseln, shortening the reach makes it impossible to achieve. Such a performance also encourages a more two-tempo Schiller execution, which many still lean towards today, but it is foreign to me.

Another minor inconsistency can be seen in that when attacking with Schiller on Langort, the authors state “haw starck mit dem schilär mit der kurczen schneid an sein swert,” which explicitly mentions the use of force. In our version, force is not as important. On the contrary, with proper mechanical execution, I do not rely on the force applied to the cut at all. A slightly different situation would be if the opponent managed to defend himself and, for example, raised his hands from Langort to Absetzen in Ochs. Then Schiller indeed needs to be given some penetrative power, and here I hit the opponent’s weak blade with Schiller and fall with the point to the lower target, almost like in Mutieren.

Such a situation, where Schiller breaks through Ochs or a similar shortened position with force, might be depicted in the following image from Ms. Germ. Quart 2020. The description before this image speaks of breaking the long point, but if we assume that the fencer in the long point expected an attack on the blade and therefore raises his hands, which subsequently proves to be a mistake as the opponent’s Schiller breaks through the position/Absetzen and hits with the point.

Image #7: Schiller breaking through Ochs

What exactly the authors meant by the phrases “betryegniß des gesichtz” and “schil mit dem gesichtt zu dem ortt vnd thun als du ym dar zu haulben wollest” (i.e., deceiving the opponent with the face) is not explicitly clear from the texts. If it is to evoke in the opponent a direct strike at the blade to provoke him into Durchwechseln, then I know far safer ways. Perhaps it is to provoke him into a counterattack with Absetzen into Ochs, where Schiller is essentially a counter-riposte.

Finally, I will mention that when we started with Schiller, I constantly tried to find in Schiller the famous Meyer image where the fencer raises his hands high above his head and steps to the side. We struggled for years to get this position into Schiller, but more or less artificially. It wasn’t until the Glasgow manuscript finally freed me from this fixation, and practice more directed towards a direct Schiller through the long point with the maximum reach. Perhaps someone will find this performance fitting. The elevated Schiller can help if the opponent strikes with hands too high.

Image #8: Joachim Meyer and his Schielhau

Despite less than 100% agreement with the texts (but no interpretation has that), this proposed version seems technically very interesting and so far undiscovered with previously unpublished advantages. Whether it is a historical version, I do not know. I am sure, however, that the performance of Schiller was not unified and standardized even in the time of the Fechtbücher.