Do Rules Ruin Fencing? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Fencing Conventions

Do rules ruin fencing? 🤔 I’ve taken a deeper look at fencing conventions from the 15th century through to modern HEMA tournaments. An in-depth analysis for anyone interested in the history and purpose of HEMA tournament rules.

This article originally began as a social media post. However, things got slightly out of hand when I started gathering relevant citations. Even in this expanded form, I haven’t managed to address all the points and questions about rules that concern me.

If readers are working from other sources not mentioned here1, I’ll gladly add them later, but I initially didn’t want to obscure the main point with unnecessary length. I haven’t explained or defined basic terms in the text, as this information should be publicly available and relatively easy to find today.2

Introduction

Every fencer or coach has their own vision of the ideal, visually impressive fencing display. However, the perception of movement aesthetics is heavily influenced by environment and individual preferences, rooted in previous experiences. Since no contemporary fencer has authentic contact with 15th-century fencing, for example, no one can claim with complete certainty how training bouts, Fechtschulen competitions, or actual duels really looked. In the current state of our discipline, requiring aesthetic standards in fencing could cause more harm than good.

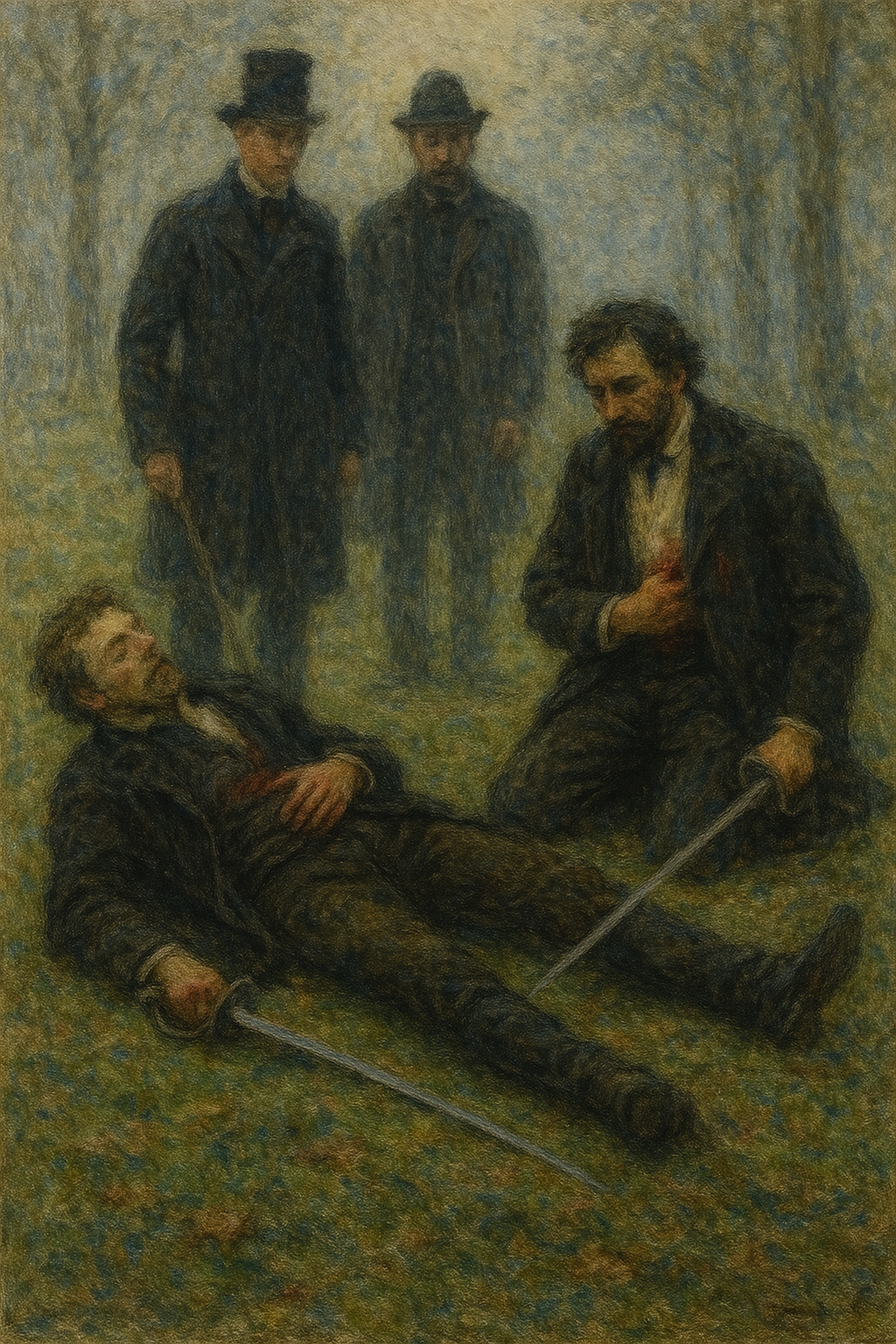

While a sprinter’s athletic excellence in breaking the 10-second barrier for 100 meters is objectively measurable, contemporary historical fencing lacks a clearly definable criterion for excellence. A duel might have served as such a measure in the past, but it’s undoubtedly positive that none of us are forced to undergo such a test today. Many claim that the search for the better fencer in sports tournaments is equivalent to historical duels, but they are stubbornly mistaken. Even historical “ernst” (serious) combats weren’t about finding the most skilled fencer.3 Current competitive interpretations attempting to simulate historical duels artificially merge two poles of fencing that have always stood in opposition.

The terms “schimpf” and “ernst” in historical context represent two complementary aspects of fencing: playful or sporting versus serious, combative. The potential fatal consequences of combat with sharp weapons required careful consideration in the case of a prearranged duel, with both parties weighing whether the potential victory was worth the risk undertaken. The participating parties considered the opponent’s sanity, their understanding of the extent of risk, and their willingness to respect certain formal or informal ethical norms.

The art of fencing was meant to thoroughly prepare a person for a real encounter with an armed opponent—to teach them to rely on proven procedures that would, with high probability, lead to a safe conclusion4 of the duel. In an actual combat, there was never an absolute guarantee of success based solely on technical superiority—on the contrary, historical sources warn of the danger of excessive self-confidence stemming from fencing training.5

Are there, then, universally valid pieces of advice that show fencers how to act advantageously in a specific situation? Isn’t the outcome of a duel primarily determined more by chance? Not everyone may agree, but such recommendations, based on experience and certain statistical observations, truly do exist. Over time, they crystallized from advice in verse form into fencing schools. Later they were reflected in general fencing theory and subsequently manifested in the rules of conventional fencing, which was meant to properly prepare students didactically, whether for a duel to first blood or for military use.6

Alongside bound conventional fencing, there has always coexisted a freer, unconventional current, represented today by sport épée, for example. Although fencing theory applies equally here, adherence to classical rules becomes secondary to the ability to effectively hit the opponent within the defined competitive framework. In other words, fence against principles all you like, as long as you can hit your opponent in time.

Conventional fencing, unlike objectively evaluated sports disciplines, has a certain degree of interpretive freedom, which some might label as subjective. In competitive evaluation according to conventional rules, the final arbiter is therefore the fencing referee and the fencing federation, which establishes and interprets the rules with all their nuances and current trends. While some aspects of evaluation—such as assessing the validity of a hit—are relatively objective, evaluating the rationality of attack, defense, and counterattack may initially seem artificial. At its core, however, it stems from historical experiences and, since the 20th century, also from modern analyses of human brain reactions to various stimuli. Without understanding these connections, what may seem “beautiful” to laypeople may be fencing that doesn’t correspond to sound fencing principles. Conversely, something perfectly effective may not always be aesthetically appealing to an inexperienced observer. This contradiction is the source of many arguments and mockery that flood the internet in HEMA-loving groups on various platforms.

Resistance to fencing theory, which is the result of centuries-long tradition, in the HEMA community that by definition stands on the legacy of the past, can be considered almost absurd. Fortunately, these are marginal countercurrents, whose representatives may have simply missed that all fencing disciplines,7 however different the weapons they use, share one common foundation. This error leads to the unjustifiably critical stance of HEMA “puritans” toward other fencing disciplines, whether modern sport fencing, kendo, or other equally professional spheres.

Historical References

Our knowledge of longsword fencing in historical context comes primarily from period fencing manuals, the so-called Fechtbuchs. These sources provide us with a relatively precise picture of the technical aspects and methods of executing individual actions, but information about how this skill was actually used in practice, how training proceeded, or what rules might have governed competitions, is largely absent from them. While we can assume that some forms of regulation existed, the Fechtbuchs themselves don’t explicitly address them. Most surviving rules from earlier periods take the form of prohibitions, specifying forbidden techniques or behaviors for which a fencer would face fines or other penalties. From this fact, we can infer that even such later-forbidden actions probably belonged to the real repertoire of fencers of that time.

Restrictions on Target Areas

The development of fencing conventions involved various restrictions, with one of the oldest being the limitation or direct prohibition of thrusting attacks. This approach, including the use of weapons with blunted or broken-off points8, appeared and disappeared in various regions until the beginning of the 20th century.9 For example, Joachim Meyer’s extensive work (16th century) systematically replaces thrusts with other, safer strikes in longsword fencing, even in situations where his predecessors would have used a thrust without hesitation.

Another key element of regulation was the definition of valid and invalid target areas. Historical records show that certain targets were considered dishonorable or inadmissible. In the well-known duel between Conrad and Heinrich from 1444, a hit to the palm was considered dishonorable, which led to the immediate stopping of the combat.

A more detailed list of forbidden techniques within the so-called Fechtschulen (fencing schools or tournaments) is provided by August Vischer in his work Tractatus Duo Iuris Duellici (1617)10. He explicitly names as inadmissible: attacks with the point (thrust), with the pommel, strikes to the groin, attacks on the eyes, pushing or even throwing stones. It’s interesting that some of these techniques, such as the thrust, pommel attack, or elements of wrestling, were part of standard training in the Kunst des Fechtens tradition.

Hit evaluation was also governed by rules. The Strasbourg fencing regulations11 from 1470 already introduced the principle that a higher-placed hit has greater value. This trend was confirmed by the Prague regulations12 a century later, which additionally emphasized the need to complete all three agreed rounds of the match, even if blood appeared after the first hit:

They should also go through all three rounds and not end the duel after the first hit when blood appears, lest one of them flee for money. The other might succeed in the second round with a “higher hit,” because a higher hit is always more valid than a lower one. They should go through all three rounds without any secret agreements.

Besides target areas and hit evaluation, the Fechtschulen regulations also addressed general behavior and equipment, which reflected the customs of 16th-century fencing:

- The custom of using excessively long gloves (up to the elbows), which could unfairly advantage the fencer, was criticized and forbidden. Instead, gloves covering only the fist were required.

- During encounters, fencers were expected not to furiously collide with each other, but to engage in combat “cleanly and judiciously,” in accordance with tradition and the art of fencing, not like “peasants.”

Similar regulated matches with a three-round format13 existed in French regions as well, known as “jeu de prix” (game for the prize)14 or “passer en défense”15 (defense after completing training). These events resembled German Fechtschulen and shared similar rules, including the frequent prohibition of thrusts and clearly defined target zones. The Paris regulations from 1538:

In this prize game, strikes are permitted from the waist upward, and from the elbows higher, up to the crown of the head, where the hit is most valuable. The highest hit is also the most beautiful and merits the most precious jewel.

— PRUNET: Ordonnance royal, 1538

Analogous rules applied in the Brotherhood of St. Michael from Lille as well. The target area was almost identical to modern sabre: hits were valid from the waist up and on the arms from the wrist (marked with three cords) upward. Head covering was mandatory and injuring an opponent resulted in fines, with the highest for bleeding on the head and lower ones for arm injuries.16

Despite the prevailing trend of restricting targets, differing opinions also appeared. Antonio Manciolino in his work Opera nova (1531) considered hands and even legs as legitimate and important targets:

“A hit to the enemy’s hand counts as a valid strike. […] It is the most significant injury, because one must strike that part of the enemy which threatens you most — and that is the hand.

A hit to the head counts for three points due to the exceptionality of this limb, and a hit to the leg for two, considering the difficulty of executing such a low attack.”

— MANCIOLINO: Opera nova, 1531

Legs as a target for cuts are also discouraged by 17th-century Henning, with reasoning that stems from the characteristics of the effect of a rapier cut. Of course, this preference isn’t valid for all weapons of that period.

It is best to cut at the head and body, but not at the legs, because by doing so one exposes oneself completely open above and thus to extreme danger, but also because one achieves little or nothing by it, especially when the opponent is equipped with large riding boots.

— HENNING: Kurtze jedoch gründliche Unterrichtung vom Hieb-fechten, 1658

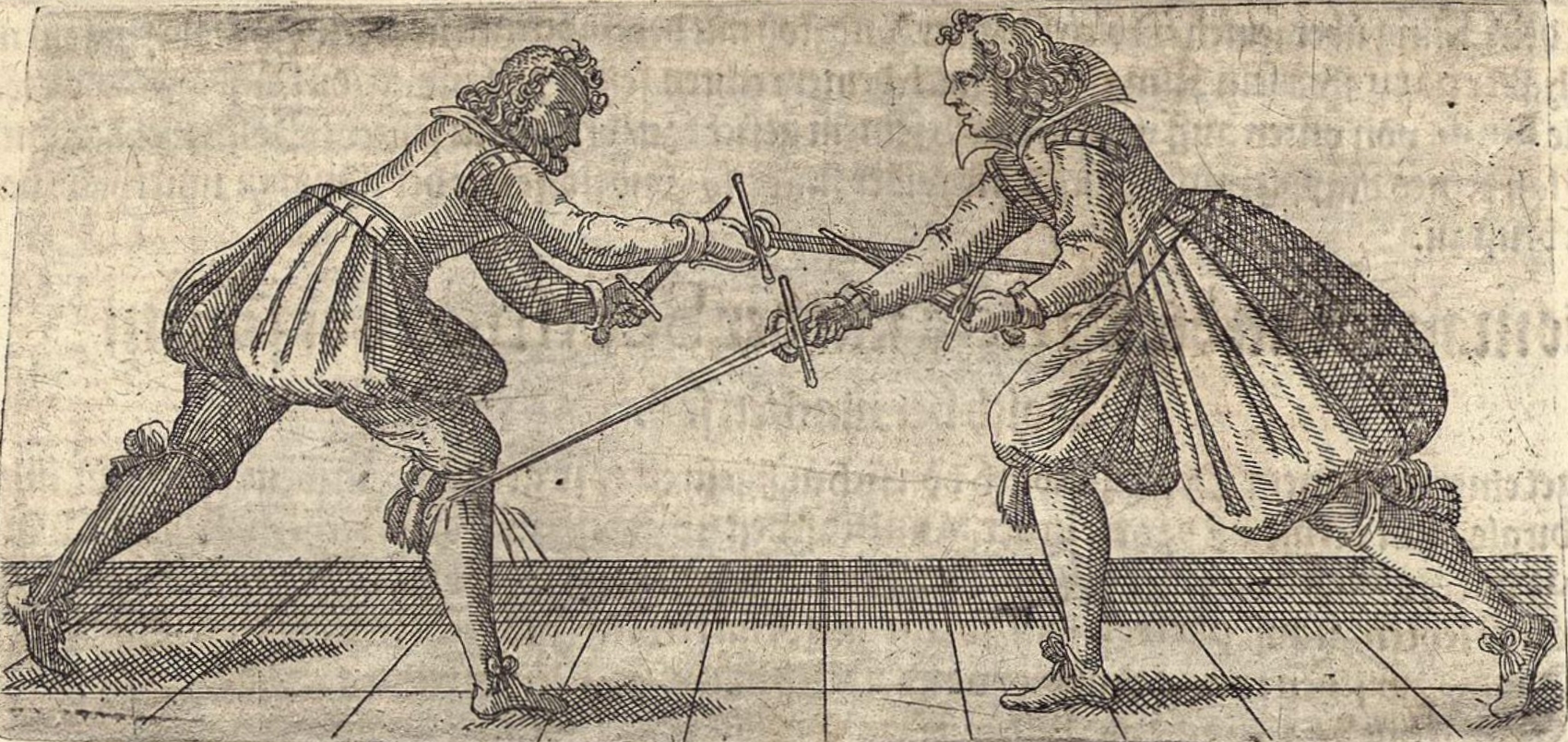

Image #1: Heussler, Sebastian: Neues Künstliches Fechtbuch - rapier cut to the leg in contrast to Henning

These examples show that conventions regarding target areas were diverse even in early fencing works, evolved over time and space, and often depended on context (tournament/schimpf vs. duel/ernst), weapon type, and local traditions. Today, longsword is predominantly fenced to the whole body except dangerous zones such as the back of the neck, groin, and feet. In Olympic fencing, foil is fenced to the torso, sabre to the upper half of the body including arms to the wrists, and épée to all targets.

Retaliation, Contrapasso, or Afterblow

In the first decade of the 21st century, the term “after-blow” spread through the HEMA community. This term was introduced by Matt Galas, who drew on historical sources from Franco-Belgian fencing guilds. The rules he described allowed a fencer to execute a retaliatory strike after being hit themselves, but this retaliation had to occur within at most one17 step or tempo.

Item: To maintain order in the game and to prevent those who are accustomed to pursuing their opponents even though they have already been hit, it has been decided that after receiving a hit, only a single step will be permitted; and if the person in question does not deliver said hit within this first step (for example, if they take two steps), this hit will be neither recognized nor valid.

— La confrerie d’armes de saint michel ou des escrimeurs lillois, 158918

The intent of this rule was to maintain discipline and prevent regulated fencing from degenerating into a chaotic brawl. A similar goal is pursued by an earlier Italian text, the so-called Anonymus Bolognese, which describes the principle of “retaliation” in the context of giucare (play, fencing with blunt weapons):

The art of fencing with blunt weapons is called giucare. The fencer must not take more than one step toward the opponent after being hit to strike them back. The reason is this: if they could take an arbitrary number of steps, it would no longer be fencing but rather actual combat. It often happens that a fencer, after being hit, angrily takes more steps, throws themselves at the opponent, and tries to hit them anywhere, just to return the blow. The judges then lose track of what actually happened, because such behavior is closer to furious combat than to controlled fencing.

Besides Anonymus, the already mentioned Manciolino expresses similar views on retaliation. In the context of his text, it’s clear that fencers were at least partially armored during fencing, and thus retaliation itself was perhaps possible thanks to body protection. He admires the strength of a fencer who, after being hit, is still capable of responding.

In later Flemish sources, the concept of “afterblow” also appears in the context of the “king of the hill” game, where it provides an advantage to the current king, while this possibility is not available to other competitors. From a historical perspective, the rule can thus be perceived more as a specific game mechanism than as a universal element of fencing practice. A similar priority for the defender, a fencer who was just undergoing public defense, is also mentioned by the Châtelet regulations in Paris. Here, however, retaliation is not mentioned, but any mutual hit. It’s natural that the defender is granted a stronger position, since they fight against many challengers. By granting the right to a double hit or afterblow, the chance increases that fencers won’t rotate like on a conveyor belt. For others, the opposite rule applied: whoever didn’t acknowledge the hit and didn’t withdraw was penalized with a fine.

But let the blows not be mutual;

If they are mutual, they have no value

For the attacker, that is true, But they serve the Defender well,

For him they count as a hit, of that there is no doubt

— PRUNET: Ordonnance royal, 1538

Despite this, in the current HEMA community it’s being overvalued, with some extreme interpretations allowing the “afterblow” to score more points than an opponent who hit first, or purposefully nullifying all hits, which fundamentally changes the character of competitive fencing.

From a technical standpoint, it’s moreover questionable to what extent the “afterblow” rule reflects actual combat dynamics. It’s not always realistic for a fencer after being hit to be able to effectively cover a subsequent “afterblow” or escape beyond its reach. Current protective equipment also significantly reduces the stopping effect of hits, creating an artificial environment where the fencer isn’t motivated to avoid being hit, but instead relies on the possibility of immediate retaliation. This phenomenon contributes to situations where three or more mutual hits can occur during one exchange, completely disrupting the readability of the exchange from the judges’ perspective, not to mention the possibly increased risk of injury.

We shouldn’t forget the not entirely negligible possibility that in a sharp duel, the struck person after being hit might not be able (or want) to continue. Executing an afterblow after being hit with a blunt sword on protective gear isn’t a sign of real resilience, unlike a hit “im Ernst,” where retaliation might indicate an ineffectively delivered first strike. A precisely executed one has the potential to physically incapacitate the opponent from completing an already prepared attack. History is indeed full of counterexamples, but di Grassi also states that this eventuality shouldn’t be excluded:

Similarly, if he prepares to thrust in multiple tempos, you hit him in a single shorter tempo. This method of defense is very useful and perhaps the best of all, because there is no man who would hurl himself headlong onto a weapon, or who, feeling that he is hit, would not immediately withdraw and hold back the already prepared blow. And although there are those who, when they feel the hit, recklessly rush forward, this happens only with few – mostly only after anger takes hold of them. But at the moment when they are hit, all retreat and are frightened, and moreover weaken with every drop of blood that flows from them……

— DI GRASSI: Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l’Arme, 1570

The potential to deliver one’s own attack or afterblow after a hand hit is found questioned even in modern times, but still with a living dueling tradition. Gustav Arlow writes about this in the chapter on stop-hits, for example, though from a sporting perspective, priority in stop-hits is given to the action that was already initiated.

The stopping thrust belongs among the most beautiful, but also most demanding methods of defense against attacks utilizing feints. Its principle lies in hitting the opponent precisely at the moment when they begin executing the attack, thereby preventing its further continuation. In a real situation with a sharp weapon, it’s questionable whether the hit opponent would even be able to continue in their original intent. In the context of sport fencing, however, only such a hit is considered a valid stop thrust where the attacker cannot reach the defender’s weapon – neither at the moment of the hit nor in the subsequent tempo.

— Arlow: A Kardvivas, 1902

Generally used “afterblow” rules don’t correspond to my view of fencing. If I were to expand our rules with an alternative principle that would support the fencer’s attention even after a successful hit, I would choose a slightly different approach. According to the new rule, the attacker who achieved a valid hit would have the opportunity to execute one more valid attack after successfully covering the opponent’s “afterblow.” In such a case, the fencer could gain two points instead of the standard one, thus rewarding their ability for prompt reaction and quality defense. At the same time, this would eliminate the possibility of abusing the “afterblow” rule and excessive emphasis on “afterblow” strikes themselves. Although this principle initially seemed like my own innovation, a very similar concept appears in the sabre rules of the already mentioned Arlow.

The Origin of Priority

There exists also another type of duel called a duel of honor, when a master is challenged by another in such a way that, in order to preserve his reputation, he is forced to accept the challenge and demonstrate his art before esteemed persons and connoisseurs of the art. In such cases, it is customary to choose witnesses beforehand – “padrini,” as well as the place, time, and weapons, and also judges knowledgeable in the art. The custom is that only the first attack and response in one tempo are permitted – and exclusively with the thrust, not the edge; because the entire exercise consists in the skill of drawing the sword, approaching the opponent with advantage, and thrusting from the waist upward. The padrini (witnesses) have the duty to separate the combatants when they exceed the fundamental distance, whether they have attacked or not, to prevent transition into wrestling (prese), where the value of the art being tested can no longer be recognized.

— GAIANI: Arte di maneggiar la spada a piedi et a cavallo, 1619

From the 17th century onward, written rules for fencing matches appear increasingly frequently. The effort for safety grew in parallel as blades gradually narrowed. Even a blunted rapier point could cause extraordinarily serious injury that couldn’t be adequately treated at that time. Target areas were progressively reduced. Simultaneous hits weren’t rare, but they were never desirable. On the contrary, all authors speak of them as an offense against the meaning of fencing. Stop-hits and attacks on preparation represented considerable risk, and therefore the principle became established that fault for a simultaneous hit lies with the one who could have reacted to the opponent’s attack and didn’t prevent the double hit.

The first explicit priority rules attempted to determine fault for such a double hit. Sir William Hope in 1692 formulated the principle that fault falls on the one who, instead of defending against the opponent’s attack, attacked themselves:

To prevent contretemps in fencing exercises, in case of a double hit, the hit should always be awarded in favor of the one who first initiated the attack, even if his opponent simultaneously executed their own attack, but without attempting to defend or parry. And this is just, because one can hardly imagine that someone would so foolishly risk their life in an actual combat, when their intention was merely to hit and not demonstrate their skill. — HOPE: The Fencing Master’s Advice to his Scholar, 1692

Hope also emphasized the need for immediate recovery after a lunge, so the fencer doesn’t remain vulnerable. Similar logic of priority for the attacker is found a century later in the Italian environment with Bremond (circa 1790). He specified that stop-hits (colpo d’arresto) or time-hits (colpo di tempo) are valid only when executed cleanly, without the author of the hit being hit themselves. In case of a mutual hit (colpo d’incontro), the one who attacked first had the right.

“On the stop-hit (colpo d’arresto)19 The counter-attack hit is executed during the opponent’s forward movement, however small it may be, if they uncover some part of the body, and against any of their strikes. When utilizing this hit, one must hit the opponent without being hit oneself, because otherwise it would be a mutual hit (colpo d’incontro), in which the one who attacked first would be right.

On the time-hit (colpo di tempo)20

The time-hit is considered the most difficult hit in the art of fencing…….The time-hit must be executed with decisiveness, and if the opponent hits you even minimally, your response won’t be valid and the opponent will be in the right. This hit is similar to the mutual hit, in which the attacker always has the advantage.”

— BREMOND: Trattato sulla scherma, circa 1790, p. 5621

Modern Aids and Safety

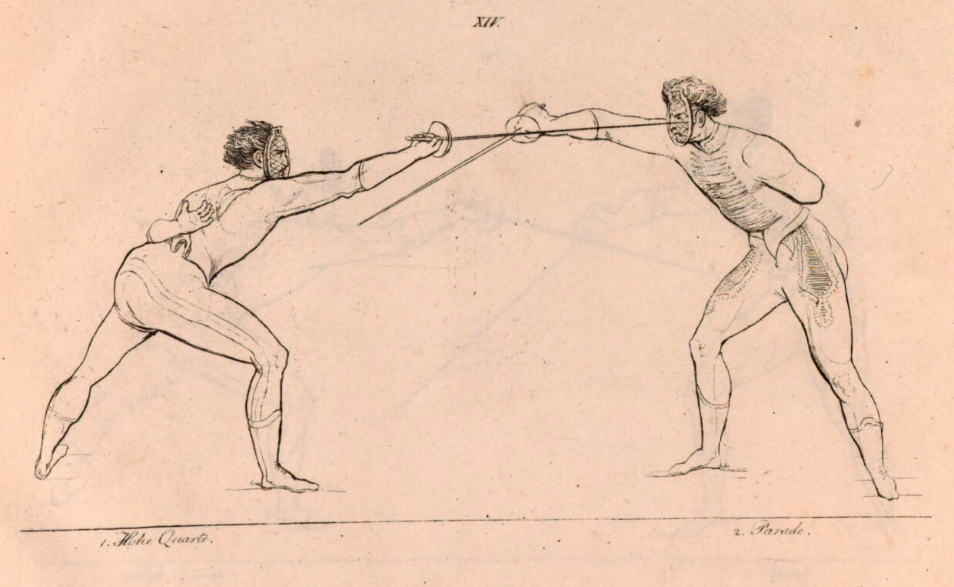

A fundamental turning point in the understanding and rules of fencing came with the introduction of fencing masks in the mid-18th century. As Captain de Bast (1836) noted, before masks, rules focused primarily on preventing serious facial injuries. Therefore, a system of alternating attacks and ripostes was often applied, and techniques like remise (renewal of attack), coup d’arrêt, or coup de temps were considered inadmissible or “irregular.”

“Before masks were used in fencing, it was common practice for fencers to alternate in attacks and ripostes – the intent of this conventional restriction was to prevent accidents that could arise in the case of freer combat. The concept of opposition (controlling the opponent’s blade) was also unknown then, so if both lunged forward simultaneously, serious facial injuries could occur. Therefore, techniques like reprise de main, remise, coup d’arrêt, and coup de temps were considered inadmissible and ‘irregular’ at that time. But since masks were introduced and with them knowledge of opposition, fencing has fundamentally changed.”* 22

— DE BAST: Manuel d’Escrime, 1836, p. 152

“From the mid-18th century, when masks were adopted, fencing began to advance again and bouts became a more faithful image of real combat. Before their introduction, bouts were subordinated to rules that, while ensuring precision, simultaneously hindered natural speed and made certain actions impossible. A fencer could riposte only when his opponent had recovered, doubling of attacks was rarely used, and time-thrusts were executed only with the greatest caution.”

— POSSELLIER: La théorie de l’escrime, 184523

Possellier confirms that masks enabled fencing to become a “more faithful image of real combat,” released speed, and allowed actions that were previously hindered by safety considerations. At the same time, however, he warned against undesirable consequences – the abuse of time-thrusts and repeated attacks, which began to be used more recklessly. Fencing gained in intensity, but according to some, lost in elegance and caution.

Reprise of the Hand with Delayed Riposte

One of the problematic aspects of fencing was the question of whether it’s possible to attack again if the opponent hesitated with their riposte. Some fencers considered it unfair if their opponent hit them with a repeated lunge before they could execute their own response. De Bast, however, argues that the fault lies precisely with the one who unnecessarily delayed their riposte:

“Many fencers are surprised that such an attack hit them, and believe that when they parried, the opponent now has a duty to wait for their riposte. This opinion is, however, just as mistaken as the objections against the so-called coup d’arrêt and coup de temps, which I have already addressed above. If a fencer receives a hit during a ‘reprise de main,’ they can blame only themselves – if they hadn’t hesitated with their response, the opponent wouldn’t have had this opportunity.”

— DE BAST: Manuel d’Escrime, 1836, p. 152

Possellier adds an important nuance to this topic when he warns against abusing delayed riposte:

“The redoublement must be executed only when the parried attack is not accompanied by a riposte. Every redoublement executed at the same time as a riposte is a fault, even if the riposte misses the target, because the attacker cannot presume such a situation, and if the riposte had hit, a double hit would have occurred.”

— POSSELLIER: La théorie de l’escrime, 1845, pp. 253-255

This approach emphasizes the need for temporal delineation of riposte validity. Possellier suggests that the riposte loses its priority if the remise hits at least one second earlier. This principle enables clear distinction between legitimate renewal and delayed riposte, which could otherwise lead to unclear and unfair exchanges. From today’s perspective, 1 second is an extremely long time and all such hits would be out of tempo even in many “afterblow” tournaments.

Priority of the Direct Line (Point-in-Line)

Later we find in manuals a new type of priority that stems from a static weapon position, not from an attack in motion. Alberto Marchionni in his rules describes and analyzes this phenomenon as follows:

§ 6. The rule holds that whoever takes the initiative of the attack, if the opponent’s blade is in a straight line or aimed at his chest, must first ensure its deflection.

§ 7. Example 1: Two fencers are on guard (within distance), with one having their weapon pointed at the other’s chest. If the first decides to attack with a feint by disengagement (cavazione), keeping their hand low, and his opponent, without waiting for further movement from the attacker, immediately lands a blow upon the first sign of movement (i.e., on the feint), in such a case, it can very easily happen that both fencers hit each other simultaneously. It must be said that the opinions of some fencing schools do not agree on determining to whom the fault should be attributed. However, I do not belong to those who would want the simultaneous hit attributed to the one who landed the direct blow, arguing that he had the duty to defend himself. But the first fundamental rule in fencing is that before attacking, it is necessary to deflect the opponent’s blade!

Can one speak of an exception here? If we admitted this and the second fencer, finding himself in the described situation, found himself hit because he threw himself onto the opponent’s weapon, can he reasonably be blamed for it? If so, then that was precisely what the first attacker should have done, and therefore it seems to me that the fault in this case falls on him, and not on the second.

§ 8. I do not contradict the principle that it is necessary to parry attacks coming from the opponent; on the contrary, the rule is that if someone is attacked, they should defend themselves. But at the same time, it must be remembered that this principle has exceptions, as I will show in the following paragraph.

§ 9. Here is the case in which the opponent is obliged to defend himself – and that is when someone attacks according to the prescribed rules, i.e., first deflects the opponent’s blade from the line. By this step, he creates an obligation for the other to defend himself. If he wants to land a counter-blow at the same time, he must do so without being hit. If, however, he were hit, the fault would be on his side.

— MARCHIONNI: Trattato di scherma, 1847, p. 36824

Marchionni also analyzes the issue of riposte and renewal, pointing out frequent situations that can lead to disputed double hits. He claims that after executing a parry during riposte, the fencer must not let their blade leave the bind, because they would thereby expose themselves to a direct hit without any further defensive measure:

It happens that after executing a parry for a riposte, a fencer withdraws their blade from the opponent’s and thereby exposes themselves so much that the opponent can immediately execute a direct hit without any further defensive measure. In such a case, the fencer who executes the remise is not obliged to parry, as they merely exploited their opponent’s mistake. However, the condition is that they must not be hit themselves. If this were to happen, then they would bear the fault, since the remise belongs among actions in tempo and must be executed precisely at the moment the opponent withdraws the blade during the riposte.

This approach is similar to the strict logic of Bremond, who emphasized the importance of tempo and immediate response to the opponent’s error. At the same time, however, Marchionni offers a clear rule: if the remise is executed correctly without a reciprocal hit, it is legitimate. If, however, a simultaneous hit occurs, the fault falls on the fencer who made a mistake in the timing of the remise. Although he prescribes how a correct foil riposte should not look, even with an incorrect one, the fault lies with the poorly timed renewal.

Near-Modern Priority Rules

Ferdinando Masiello, in his work La scherma italiana di spada e di sciabola (1887), and Gustav von Arlow, in A kardvívás (1902), offer systematic solutions for evaluating double hits in fencing. Both authors recognize that a simultaneous hit results from a deviation from proper fencing principles25, and they introduce rules aimed at reducing avoidable double hits. Masiello, following in the footsteps of Possellier, establishes the principle of temporal priority, according to which a riposte must be executed immediately after the parry26. According to Masiello, responsibility for a double hit is assigned as follows:

- If a fencer delivers a stop-hit (arresto) or a hand attack regardless of the opponent’s action, the fault lies with them.

- If they attempt to deflect the opponent’s blade but proceed with their attack without having actually diverted it, the fault is theirs.

- If they attempt a stop-hit against an opponent who continues to feint without any clear intent to strike, both fencers are at fault.

- If they launch a riposte without first having found the opponent’s blade during the parry, they bear the responsibility.

- If they fail to remove the opponent’s blade from the line before their own attack, both fencers share the fault.

- If both fencers lunge simultaneously after a long pause awaiting an attack, responsibility is shared.

Fifteen years later, the Hungarian fencing master Gustav Ritter von Arlow built upon this principle of attack priority. In his manual A kardvívás, he likewise addresses the problem of the double hit and stresses that such an outcome is undesirable and results from the error of at least one participant. Arlow introduces the term utánvágás (literally “cut following a hit,” i.e., afterblow) for an additional cut landed after the fencer has already been struck. In a sport bout (assaut), such a late hit, according to Arlow, should not be counted—it arrives too late. He does, however, caution that in a real duel, even such a blow could cause injury. Arlow thus appeals to the fencer’s sense of responsibility: even in training, one must not remain undefended after being hit under the assumption that “a double hit doesn’t count.” On the contrary, a skilled fencer will always ensure their defense even after their own successful strike27, to avoid the so-called ambo (Latin for “both”). His system for evaluating simultaneous hits in sport fencing closely follows Masiello’s principles and brings fencing closer to its modern understanding.

A) The attacker is considered at fault for the ambo, if:

- The attacker runs into the opponent’s extended point.

- The attacker launches an attack, the opponent dodges and counters, and the attacker continues regardless.

- During their attack, the opponent performs a stop-cut or stop-thrust; the attacker interrupts the action to parry but then completes the attack regardless.

- While feinting, the attacker contacts the opponent’s blade, prompting an immediate riposte, but continues with the attack anyway.

- The attacker, after feinting, receives a stop-cut or thrust and then lands their own hit, with more than one tempo separating the two actions.

- The attacker initiates with an invitation, bind, or another provoking action, but fails to parry and is hit.

B) The defender is considered at fault for the ambo, if:

- They cut or thrust into the opponent’s simple attack.

- They attempt to stop the attacker with a stop-cut or thrust in tempo, but the attacker continues uninterrupted and scores with no more than a one-tempo delay.

- After a successful parry, they fail to immediately riposte, allowing the opponent to execute a remise and score.

- Instead of parrying, they attempt an evasion combined with a stop-hit in tempo but are also struck.

C) Both fencers are considered equally at fault for the ambo

- The attacker performs excessive, unjustified feints, while the defender retreats and responds with a late attack.

- Both fencers attack and hit simultaneously.

The approaches taken by Masiello and Arlow represent advanced historical attempts to resolve the problem of double hits. Across 19th-century fencing literature, these rules are more or less widely accepted and formed the foundation of modern conventional fencing rules based on the right-of-way system, where responsibility—and therefore the point—is clearly assigned, though sometimes asymmetrically, in the case of simultaneous hits.

The question that remains, then, is how modern HEMA—especially in the discipline of longsword fencing, where varied approaches to scoring are frequently used—reckons with this rich and complex historical context in the development of priority rules.

Modern Rules for the Longsword

A commonly resonating claim in current discussions is that “a good fencer can succeed in any rule system.” However, it would be wrong to conclude from this claim that rules represent only formal regulation without fundamental impact on the development of fencing technique and tactics. My stance is opposite: properly designed rules actively support the development of technically and tactically advanced fencers.

A generally recognized principle is that tournaments consist of many matches and each match has multiple exchanges. Attempts at single-exchange matches that would imitate a real duel are clearly unsuitable for competitive fencing. When judging hit validity, the referee enters who ends the exchange at the moment they identify the first valid hit, or leaves minimal time interval for the hit person’s reaction, limited to at most one fencing tempo—that is, one indivisible action.

One of the main contentious points when creating rules is the question of evaluating hits in situations where both sides are touched during an exchange; double, incontro, ambo, Mitstoß. Situations where only one side is hit aren’t subject to such controversy and the only meaningful question is whether the hit was valid or invalid, or whether there was some disciplinary offense or other violation against the spirit of fair-play. Doubles and double hits are the subject of general HEMA discussion since the emergence of the competitive scene. In times when the core of HEMA community activity lay in reconstructing original techniques, the double as a phenomenon was more or less overlooked and in the context of research without proper practice, this question didn’t really make sense.

The collision with the reality of tournaments or even friendly matches, however, caused these situations to no longer be ignorable. The first logical justification for why doubles happen was to blame the lack of training techniques or misunderstanding of fencing masters. The real answer, however, lies elsewhere. No fencing system or school protects against double hits, and if the other party isn’t a cooperating subject, then I dare claim they will always occur. What we can influence is their frequency and how we approach them and learn from them.

Historical sources make it clear that this problem is not new—fencers have been concerned with it since at least the 16th century. In the context of a duel, a double was extremely undesirable for both parties. In sport, it is a situation we can learn from without fatal consequences. The key question remains how to analyze such exchanges and what adjustments we can make to minimize their occurrence.

Preconditions for a Duel

Before entering a duel, several key preconditions or factors must be considered. Evaluating them helps a participant assess the risk-to-gain ratio—whether in terms of restoring one’s honor or resolving a conflict.

-

Cause or pretext (Casus Belli): There must be a sufficiently serious reason for at least one party to willingly accept the risks involved in initiating or accepting physical confrontation in the form of a duel. Without a compelling cause, the duel loses meaning and becomes nothing more than senseless violence.

-

Opponent’s sanity and rationality: Both parties should be of sound mind, capable of rational judgment, and aware of the consequences of their actions. It is essential to assess whether one’s opponent understands the seriousness of the situation. A duel with someone showing signs of instability, extreme emotional volatility, or irrationality introduces unpredictable and often unacceptable levels of risk.

-

Mutual respect or instinct for self-preservation: Ideally, both duelists should have a genuine interest in surviving the encounter with minimal harm. A basic assumption (though not always honored in practice) is that the goal is not mutual destruction at any cost. While deliberately trading one’s own safety—e.g., taking a non-fatal hit to land a more damaging one—can be a tactic, in the context of a regulated duel of honor, I view this as undesirable.

-

Fair play: A basic level of trust must exist that the opponent will respect the agreed-upon or generally accepted rules and customs of the duel. If there is reasonable suspicion of deception, dishonesty, or a disregard for the conditions of the fight, the risk increases dramatically, and the concept of a fair duel is undermined.

Foundations for Rule Design

The creation of effective and meaningful rules for fencing matches or tournaments should be based on several core principles. These principles ensure that rules not only regulate the bout but also support the development of skilled fencers and uphold the spirit of the discipline. Key foundations include:

-

Safety and assessment: Rules must provide a framework that ensures safety while allowing for the objective evaluation of each fencer’s technical, tactical, and athletic performance.

-

Combat relevance and habits: Although competitive fencing rules are not intended to simulate real combat directly, they should help fencers identify and develop habits and techniques that could, in principle, be applicable in realistic combat scenarios. Rules should support heuristics that reduce exposure to risk, even though no strategy guarantees success or eliminates the possibility of mutual hits.

-

Accountability for mistakes: Fencers make errors. Rules should clearly establish which party bears greater responsibility in problematic situations (especially double hits). They should reward safe and technically correct behavior, while penalizing actions that would be dangerous or undesirable in a real duel.

-

Link to training: Rules alone have limited effectiveness if not supported by a training system that teaches fencers how to operate within the rules and achieve the goals the rules are designed to encourage.

-

Protection against rules exploitation: Rules should be designed to limit the exploitation of tactics that may comply with the letter but violate the spirit of the rules or contradict sound fencing principles—so-called “gaming the system.”

-

Assumed seriousness of hits: Rules should implicitly reflect the assumption that in a real context, any valid hit could have serious consequences. This encourages respect for the opponent’s actions and reinforces the importance of defense, even when fighting with blunted weapons and protective gear.

There are three further expectations of rules I haven’t included in the list above: spectator appeal, support for historically informed fencing, and simplicity for both fencers and judges. I don’t consider any of these to be primary criteria, though simplicity, at least, must be factored in to some extent.

Rules must be simple enough that trained fencers and judges can understand and apply them in practice—specifically, to recognize the situations the rules describe. It is not necessary for every participant to grasp the full rationale or historical evolution28 behind each rule formulation, just as most athletes today are unfamiliar with the origins of tennis scoring (15, 30, 40) or the development of the offside rule in football.

What’s important to remember is that rules should not be simplified to the point where they dictate the entire character of the discipline. If two inexperienced fencers meet and exchange actions that result in hits on both sides, chances are neither will be able to explain what happened or why29. To them, it will likely be: “We both attacked and somehow hit each other.”30 At most, they may notice who landed the hit first. This inability to analyze the situation makes it hard for them to learn from it. The only feedback they receive is whether they managed to land a clean or significantly earlier hit. Any additional context the referee can provide when describing the exchange helps them identify the cause of the double hit more quickly and learn how to avoid it in the future.

For this reason, the demand for simplicity is only justified to the extent that it does not prevent fencers from applying more sophisticated tactics. Exchange evaluation should not place technically simplistic, impulsive actions on the same level as thoughtful, tactically sound solutions—doing so erases the difference between them.

As for spectator appeal (and appeal to fencers), it can help expand the reach of the discipline, but it must not take precedence over fencing principles. Some may argue that aesthetic criteria have historically played a role in match evaluation. I don’t believe, however, that fencing—particularly longsword fencing—is today such a unified or mature discipline that it could support figure-skating-style competitions. From personal experience, I know how subjective such judging can be, and I would consider it suitable only at the club or local level.

In classification fencing, aside from hit outcomes, what is assessed is primarily the fencer’s effective skill, then the beauty and correctness of movement, mental concept, and precise adherence to fencing rules. Fencers are scored on a scale from 1 to 10, or 1 to 20. The average score determines ranking. Whoever receives the highest score is the best.

— BARTUNEK: Ratgeber für den Offizier, 1904

On the other hand, support for historical techniques is, in my view, not a valid requirement—and no modern rule set for historical fencing should hinge on fidelity to a particular historical tradition. If a given historical school is genuinely effective, its techniques will naturally make their way into fencers’ repertoires.

Errors and Responsibility for the Double Hit

Every fencing exchange involves mistakes, which may lead to a hit on one or both sides. In the case of a mutual hit (double), the goal of analysis is to identify the errors made by both fencers and determine which of them was the primary cause of the situation—that is, who bears the greater responsibility. While the exact formulations may vary across rulesets, the fundamental principles for assessing fault remain largely the same. The following is a summary of common mistakes that often lead to double hits. In most cases, one fencer’s error is more serious than the other’s:

- I run into the opponent’s extended and clearly presented point while launching my own attack.

- I ignore an ongoing threat to an open line and decide to strike anyway, without adjusting to the situation.

- I prepare a multi-hit combo (two or more attacks) without regard for my opponent’s reaction, or I fail my attack and don’t defend myself from the counter.

- I attempt to suppress the opponent’s blade with a cut or bind, but the attempt fails—and instead of recovering, I continue my attack in panic.

- My opponent removes my blade from the centerline, and instead of defending or resetting, I launch my own attack regardless.

The above list obviously doesn’t contain a complete inventory of errors that a fencer can make in an encounter. It also doesn’t capture technical errors that must not go unnoticed in training but should play at most a secondary role in match evaluation.

Error 1: Line

Running into a static, extended point is a clear example of tactical failure—or a lack of basic fencing competence.

Discussion31: While the principle is clear in theory, its application is more complicated in practice. Rarely is the defender’s line held completely static throughout the attacker’s action. Often the defender responds actively—by extending the arm or advancing from their line—transforming the situation into attack vs. counterattack. In such cases, the attacker isn’t simply “running onto a line,” and the outcome must be judged according to rules governing attack vs. counterattack (e.g., right-of-way or tempo), rather than simple fault assignment. The key is distinguishing whether the defender held a passive threat or actively launched into the attacker’s action.

Error 2: Ignoring an Ongoing Attack

The essence of fencing is often captured in the maxim: “Hit and don’t get hit.” Failure to respond to an obvious threat and instead willingly exposing oneself is a serious breach of fencing logic.

Even a suboptimal attack becomes a committed action—especially if it closes distance or presents a credible threat. If the defender is aware of the attack and chooses not to act against it, they’ve made a conscious decision to risk being hit. Criticizing the attacker’s imperfect technique doesn’t absolve the defender of their obligation to respond. On the contrary, it’s precisely those technical flaws that offer opportunities for effective defense—via parry, controlled opposition, or stop-hit.

Discussion 1: Some students of the KdF (Kunst des Fechtens) tradition might object that their system emphasizes counterattacks and attacks into preparation more than parry-riposte sequences. However, the Zettel and its glosses were written for fencers already proficient in fencing fundamentals32, including parry and riposte. Counterattacks are an advanced tactical theme and the possibility of a double isn’t an acceptable outcome.

Discussion 2: Another argument might be that if the defender can respond during my attack into an opening, I didn’t prepare the attack well enough. This is a fair expectation—and one that’s often encoded in unconventional rulesets33, which penalize both fencers for a double, but less so the one in the lead (i.e., the one with more clean points).

Special Note on Compound Attacks

A common misconception is that a double hit during a feint-based attack is always the attacker’s fault. This isn’t true. Feints are part of attack preparation. If the defender strikes during the initial feint phase—before the final attack is launched—that’s a valid stop-hit, and the attacker is at fault. But if the defender ignores the final committed action and attempts a simultaneous strike instead of defending, the responsibility is theirs.

This principle of correctly timing a stop-hit against a feint is clearly expressed by Francesco Antonio Mattei:

I recognize, therefore, that against all feints, the opponent can defend with certainty using tempo, which—as a perfect action—is rightly praised by all. But one must take care to use it at the very first movement of the feint—assuming the fencer steps into distance at that moment. In such a case, as I have said, they should strike with a direct thrust and simultaneously pull their torso out of reach. Otherwise, if they attempt to strike on the second motion of the feint, they will either miss—or if they hit, the result will be a double.

— MATTEI: Della scherma napoletana, 1669

Error 3: Remise and Continuation

Offensive combinations belong primarily in drills—and should probably stay there. Combos have no place in free fencing if executed “with eyes closed,” without observing the opponent’s reaction, or without planning second or third intention. If every strike in a sequence is meant to land on its own (i.e., first intention34), such behavior could fairly be described as suicidal.35

Discussion: If we draw from KdF material, we find the idea that Nach (after) defeats Vor (before). Authors recommend that if the first attack fails, the fencer should follow up—only if the initial attack forced the opponent into reactive, disoriented defense. Preferred follow-ups are actions like Zwerhau, which simultaneously threaten and cover lines.36

The same texts also note37 that after a successful parry, one should immediately riposte, ideally maintaining the point within half an arm’s length from the opponent’s chest or face—so they can’t renew their attack first.

At first glance, there appears to be a contradiction between renewing one’s attack and immediately riposting. But there’s no mention of simultaneous hits. Instead, emphasis is placed on timing, control, and discipline. These aren’t sport rules, but practical advice for hitting without being hit.

Do KdF sources express a preference between remising and riposting or securing a counterattack? Not explicitly. But fencing logic certainly does. It aligns with the understanding later formalized in priority-based systems: a clean, well-timed riposte is a valid, automatic reaction—just like a covered counterattack. Thus, a fencer can’t assume their opponent won’t respond. Any attack must account for this possibility; if it doesn’t, it’s flawed.

If the defender hesitates in their riposte—due to a well-prepared attack, intimidation, or their own mistake—the attacker may justifiably continue, ideally with opposition.38

Error 4: Failed Blade Attack

Many fencing traditions consider blade attacks inherently suboptimal—since you’re not threatening the body. That said, blade actions such as binds39 or beats40 can be necessary to create a safe opening. A well-executed blade attack may offer momentary control or time to act. However, if the blade attack fails and the opponent regains initiative, continuing one’s attack without adjusting to the new threat is a critical mistake.

Error 5: Displaced Blade

If the opponent has removed or neutralized my blade, they’re fully entitled to exploit that advantage. Attacking into this moment—when I’ve been bound, displaced, or otherwise disarmed—is a misunderstanding of the danger I’m in.

General Principle of Fault

In evaluating simultaneous hits, a core principle should apply: if one party has the opportunity to prevent a double, they are morally obligated to do so.

Within the safe environment of the salle or gym, clad in modern protection, our survival instincts grow dull. Fencing may not faithfully simulate a duel, but it must not ignore its essential values. Provoking a double is easy—and in sport, it carries no real consequence beyond what the rules impose. Yet those rules are meant to support fencing as a tactical, technical, and athletic pursuit—and to keep it from drifting too far from its original purpose.

This principle of responsibility for doubles is today known as priority, or right-of-way.

The rules on double hits must be formulated in a way that respects the natural boundaries of combat. Anyone who has served as a second in a sabre duel knows that even a weaker fencer may suddenly produce effective, well-timed parries under the stress of a real confrontation—because the awareness of genuine danger forces instinctive reactions.

— BARTUNEK: Ratgeber für den Offizier, 1904

Hierarchy of Evaluation

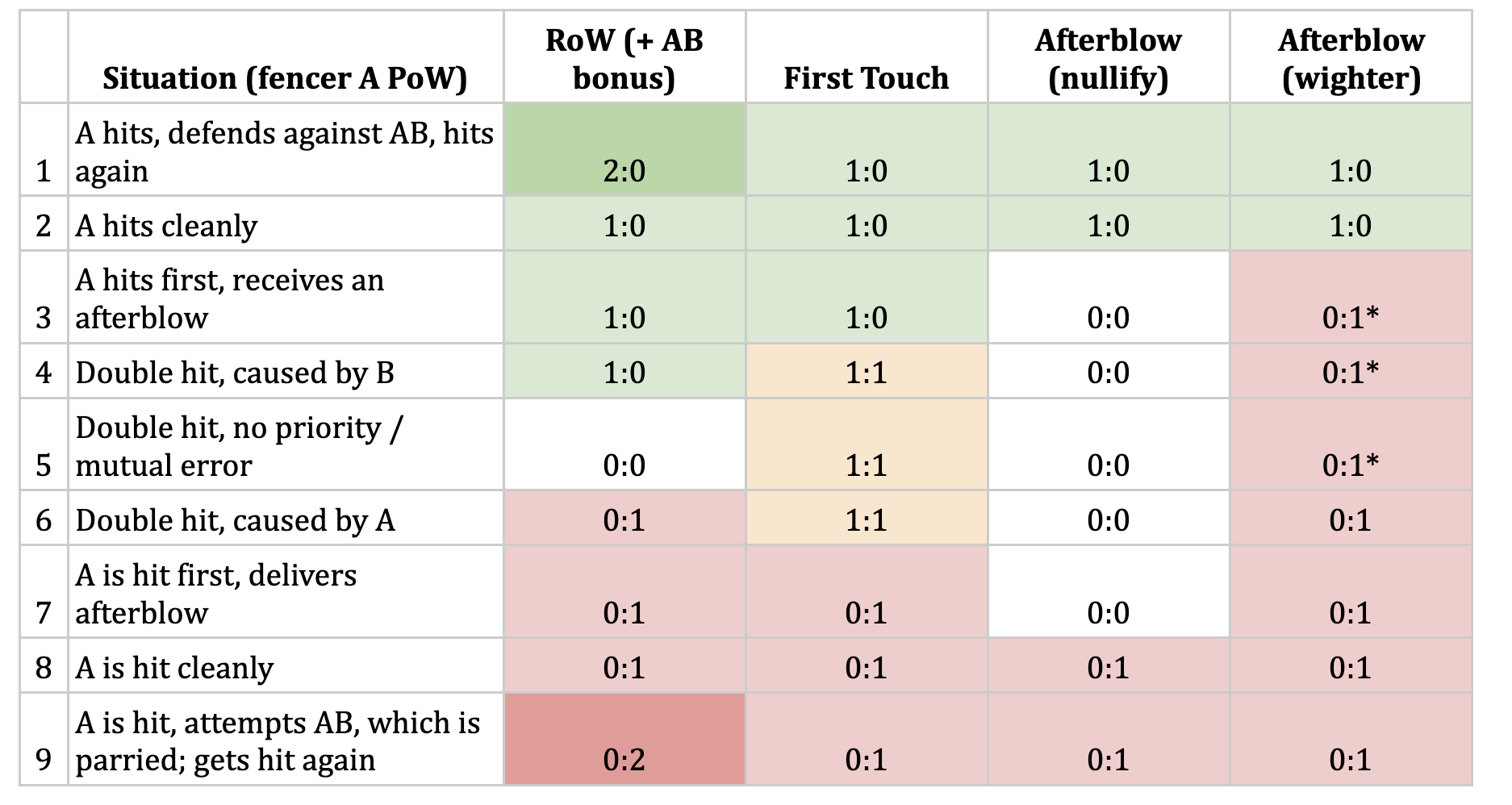

From the attacker’s perspective, exchanges can be ranked in the following order of value:

- I land a hit, prevent the afterblow, and strike again.

- I land a hit and am not hit in return. From a dueling perspective, this is equivalent in value to point 1, but in terms of fencing art, the first is a level above.

- I land a hit but am struck in return with an afterblow.

- I land a hit while being hit simultaneously. According to the principles of fault in doubles, my opponent is considered responsible.

- Both of us strike simultaneously, with equal fault.

- Both of us strike, but I am responsible for the double.

- I am hit, but I manage to land an afterblow in return.

- I am hit without striking back.

- I am hit, strike an afterblow, and my opponent parries it and hits me again.

Note: The score values in the final column are illustrative only and would depend on the specific ruleset used (e.g., different weightings for head vs. hand strikes). Question marks at 2:0 and 0:2 indicate a proposed bonus system by the author.

This ranking does not fully account for rulesets that assign different values to different target areas. Choosing an appropriate scoring method is often more a matter of judgment than strict logic. In my view, the first two columns represent systems well-suited for training and fostering a healthy fencing mindset. The third column is still acceptable; the last, however, is outright harmful.

For feedback purposes, fencers might perceive all entries within a color band as equal—fostering the illusion that all situations within that band have the same tactical value. Rulesets based on right-of-way are best suited for beginners and intermediate fencers, as they benefit most from the clear logic of “who has the right to strike.” Experienced fencers already internalize this logic and don’t require it to be made explicit. In contrast, rules with afterblow allowances may confuse less experienced fencers—especially if they haven’t yet developed an intuitive grasp of sound fencing principles.

Gaming the Rules

No ruleset is immune to exploitation. The goal of careful rulecrafting and precise definitions should be to minimize this risk—though in a competitive environment where fencer quality and training intensity increase every year, that’s easier said than done. But what is “gaming the rules”? It’s behavior that formally complies with written rules while contradicting the spirit or underlying principles of fencing.

A classic example is the use of one-handed strikes to extend reach. While effective in competition, such strikes would be risky in a real duel—where losing grip on your weapon might be fatal. Likewise, a throw might seriously injure your opponent, but it’s rarely included in one’s actual dueling repertoire. For this reason, discussion around deprioritizing one-handed strikes is legitimate—and some rulesets already do so.

Another example of potential abuse—often raised in relation to right-of-way rules—is the “suicidal attack.” However, in HEMA tournaments, I haven’t observed this as a widespread issue. At least in strikes to the upper body, these don’t seem prevalent. I’ve noticed a few questionable exchanges involving lower targets41, which is why I support discussion on deprioritizing—or even removing—low-line targets from scoring zones. As for suicidal attacks in general, my public request for video evidence yielded very little material suggesting systematic abuse.

Where I do see a risk is in attacks that only appear to meet the criteria for right-of-way but are actually false commitments—feigned all-in attacks, intended to bait a counterattack. Protection against such behavior depends heavily on the referee, who must judge whether the attacker truly committed or merely simulated the action. This places a high burden on the referee, who must be deeply familiar with fencing principles and ideally also a high-level fencer.

“First-touch” rules are much simpler—but can also be gamed, often through late counterattacks or counter-tempo actions. As Possellier noted, this problem emerged especially after the introduction of fencing masks. Modern sport fencing has tried to mitigate it by shortening the so-called lockout time—the window in which hits on both sides are registered. In foil, this is currently 40 ms—a window so short that in real combat it would almost always be simultaneous. If the interval were longer, such as 200 ms (as seen in some rulesets), it would be far easier to exploit. Our own tests showed that if a fencer commits to “doubling” and has one full tempo to execute it, it’s nearly impossible to avoid a double. In fact, the cleaner fencer may end up the only one struck—precisely because they didn’t anticipate being punished for their good fencing.

“We can assure you that such a desperate man has, more than once, succeeded—landing a counterblow and striking his opponent alone, because the opponent, lacking sufficient caution, tried to defend too late…”

— KAHN: Anfangsgründe der Fechtkunst, 1739

In a sport setting, “first-touch” rules are useful for encouraging solid preparation—but can also lead to bad habits if taught first.

“Even if someone were to find themselves in a real duel with foils, such simultaneous hits would be particularly dangerous. And even if someone objects that they would behave differently in such a situation—well, habits are powerful, and they may end up acting on instinct despite themselves.”

— KAHN: Anfangsgründe der Fechtkunst, 1739

A major weakness of first-touch systems is the lack of a reliable objective mechanism for measuring timing differences—so that double-hit criteria are not uniformly enforced across all rings.

Much has been written about abuse of afterblow rules, and since I’m personally not a supporter of such systems, I’ll leave their defense to others. The key question remains whether their originally noble and historically valid purpose has been reduced in today’s tournament scene to little more than a way to mask one’s own mistakes. We also can’t deny that fencers are sometimes swept up in chaotic exchanges with multiple hits and doubles, which are hard to judge fairly. This phenomenon still deserves technical debate and further research based on robust tournament data.

“One often finds that even those with some training let themselves be overtaken by anger or rashness—and instead of defending, they strike at the same time as their opponent… Even though someone who hits simultaneously with no defense gains little from it, they are still content if they manage to land a hit. How dangerous this decision is, anyone can easily imagine—and thus understand how two people might wound, or even fell, each other simultaneously.”

“…those who are weaker and unable to prevail through skill often resort to Mitstoß—and thereby learn something that leads more to their own ruin than to their benefit.”

“In these simultaneous hits, whether inside or outside, one cannot overlook the fact that many fencers take particular pleasure in striking the opponent even as they themselves are struck—believing that this way, their opponent has gained no real advantage.”

— KAHN: Anfangsgründe der Fechtkunst, 1739

Validity

The discussion about the validity of hits falls outside the main focus of this article, so I will address it only briefly. In order to fairly award a point in a sporting bout, we must be able to evaluate whether a hit occurred, and whether that hit would have had injury-causing potential. Under current judging practice, which relies entirely on visual observation, it isn’t possible to consistently and reliably assess the likely effectiveness of a hit.

For this reason, I favor a presumption-of-quality approach. If a fencer’s movement clearly shows intent and is executed in space with attributes consistent with a real cut or thrust, then the absolute force is not the decisive factor. A valid cut, then, is one with sufficient chamber and blade contact along a meaningful length. A thrust is considered valid if it has a clear forward trajectory, or causes either blade bend or a recoil from the mask.

Cuts are rarely observed under tournament conditions—typically only as a last-ditch effort to salvage a failed attack, and are seldom credited as valid.

One historically emphasized condition for the validity of a cut is correct edge alignment42. In practice, however, enforcing or even reliably identifying edge alignment during bouts is extremely difficult. Even a few degrees off can significantly reduce effectiveness. While it is crucial to insist on correct edge use in training, I currently advocate ignoring this criterion in competition—because a hit is a failure either way, regardless of whether it landed with the edge or the flat.

Should technology in the future allow for consistent and reliable evaluation of hit quality, it would undoubtedly be a step forward.

Training Framework

Conventional rules say nothing about a fencer’s technical repertoire. In my opinion, they don’t even depend on the weapon used—be it longsword, smallsword, rapier, or dueling sabre. The underlying principles remain constant, even if some techniques are easier or faster to execute with particular weapons.

Rules for competition should function as a framework that allows the coach to constructively guide the didactic process—not as boundaries that every attempt at pedagogical creativity must crash against. Ideally, training exercises should go beyond the rules of priority. Why? Because a hit isn’t always valid, it doesn’t always count, and the referee isn’t always in the right position—fencing is a sport, not a microscope. That’s why defense after a hit still matters. If not for the referee, then at least for your next second of life in a hypothetical duel—or simply the satisfaction of training fencing as a complete art.

Likewise, one shouldn’t underestimate preparation before the attack. An attack without preparation rarely represents true fencing skill—especially when the opponent easily counters a tempo earlier. And while in training that might just be another double, im Ernst it’s the end.

If your fencing system emphasizes counters, prepare for extra work—counterattacks must be earned, and they must avoid being hit in the process.

If your focus is on defense and riposte, train for rapid responses—ideally before the opponent even realizes their attack is over. Don’t forget about feints either. Even the fastest riposte is too late against a perfectly executed deception.

If your specialty is attack renewals, frame them with second intention: apply pressure, force a reaction, manipulate expectations. But don’t try to play the game of “one more tempo” — it’s pointless. A tenth of a second won’t save you. And the result will be, yes, another double. As we’ve seen, historical treatises had little love for doubles—not just because they ruin the aesthetic of an exchange, but because historical masters didn’t view mutual death as a draw.

The tournament was held with 690-gram old-fashioned sabres. The rules were very loosely defined. Only the result of the hits was considered—that is, the number of hits; doubles were counted as hits for both fencers, and it was agreed that flat strikes should not count. That was basically it. This stands in stark contrast to the Italian school, which distinguishes between sport fencing and dueling fencing, and which uses precise “assaut” rules to evaluate doubles—allowing the match to unfold in a realistic manner. Every sport has its own precise rules. While the Italian school uses a dozen rules to evaluate doubles, the old method knows only two. Of course, in the Italian school, if both attacks land in natural tempo (tempo communi), the hit is counted for both. … As expected, the tournament ended in complete fiasco and general disappointment. … Only 32 participants registered. Although the jury included some respected gentlemen, they were by no means fencing authorities and—due to their lack of knowledge—were not competent to fulfill their judging role. Where else have you seen a jury position themselves on only one side of the stage, as happened here? From such a place, they could see nothing at all.

The course of the tournament painted a very particular picture. Instead of structured assaut exchanges, the fencing stage presented wild scenes more akin to bullfights, where the rule was: “cut, cut, and cut again.” Eight of ten exchanges were doubles.

— BARTUNEK: Ratgeber für den Offizier, 1904

…when an opponent performs a thrust while stepping forward with the front foot, there is nothing stopping the other from attacking at the same time. The result is that both launch their strikes, their points move toward a hit, and neither blade defends against the other—so both fencers are struck.

— MARCELLI: Regole della scherma, 1686

Conclusion

In writing this article, I’ve tried to consider historical treatises, the views of fencers across centuries, and my own experiences within the HEMA community. The fencing conventions developed over time teach us to respect rules—but also to recognize their limits. Amid the flurry of motions that may appear chaotic, there is an underlying system and hierarchy built on respect for one’s own health and that of the opponent.

Over the centuries, rules evolved with the aim of balancing safety and realism. Some rules that were once relevant are now mere historical curiosities. Others continue to resonate and shape our present-day fencing. Modern debates about afterblow and right-of-way show just how vividly we still engage with these historical concepts—and that, more than anything, affirms the vitality of the HEMA movement. No trendy ruleset or “new” weapon will bury this discipline as long as its core continues to be shaped by rational dialogue.

HEMA’s position between modern sport and martial tradition is the root of many internal tensions—especially regarding the direction this discipline should take. One of the great challenges ahead is to find a balance in competitive rules that fosters technical and tactical excellence without losing touch with the historical heart of the art.

Every fencing coach carries responsibility not only for their students, but for the integrity of the discipline itself. Methodological mistakes can affect its development for years—far more than any flawed interpretation of a secret Kurtzhauw.

The beauty of fencing, which captured and held me, lies in this continual process of exploration, discovering connections, questioning assumptions, and reevaluating everything in cycles. That’s why fencing will never be “just a sport”—it will always be a path of personal growth.

Literature

Anonymous author. MS 3227a (Nürnberger Hausbuch). 14th century, https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/MS_3227a

Bartunek, Jozef. Ratgeber für den Offizier zur Sicherung des Erfolges im Zweikampfe mit dem Säbel [Advisor for the Officer to Secure Success in the Duel with the Sabre]. Esztergom, 1904, https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/detail/o:8135

Bremond, Alexandre Picard. Trattato sulla scherma: Principii e regole per ben maneggiare la spada [Treatise on Fencing: Principles and rules for handling the sword well]. Circa 1790, https://books.google.sk/books?id=WIaXVg6yx2YC

de Bast, Capitaine. Manuel d’Escrime, ou l’Art de se défendre et d’attaquer avec le sabre et l’épée [Manual of Fencing, or the Art of defending and attacking with the sabre and the sword]. Paris: Imprimerie de J. Tastu, 1836, https://books.google.sk/books?id=fNM9AAAAcAAJ&hl=sk&pg=PR3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Di Grassi, Giacomo. Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l’arme si da offesa, come da difesa… [Reason for using arms securely both for offense and defense…]. Venezia: Giordano Ziletti, 1570, https://archive.org/details/ragioned adopra00gras

Dupuis, Olivier. A fifteenth-century fencing tournament in Strasburg. In: Acta Periodica Duellatorum, vol. 3, 2015, pp. 67–79, https://doi.org/10.1515/apd-2015-0003

Dupuis, Olivier. Organization and Regulation of Fencing in the Realm of France in the Renaissance. Acta Periodica Duellatorum. 2. 2014, https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/6639/663972470007.pdf

Gaiani, Giovanni Battista. Arte di maneggiar la spada a piedi et a cavallo [Art of handling the sword on foot and on horseback]. Venezia: Giacomo Fontana, 1619, https://books.google.sk/books?id=5tt7MwEACAAJ&hl=fr&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false

Henning, Erhardus. Kurtze jedoch gründliche Unterrichtung vom Hieb-fechten [Brief yet thorough instruction on cut-fencing]. Leipzig: Henning Groß, 1658. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=ZbNJzFsFMugC

Hope, William. The Fencing Master’s Advice to his Scholar. Edinburgh: James Watson, 1692, https://books.google.sk/books?id=enkOtbtfFgIC&hl=sk&pg=PP7#v=onepage&q&f=false

Hurley, Emerson. Conventions Safari. 2024. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1bciZjeJOCNWA4X4k1-M4Tp0e7wtzRwc1i1MvNznWeOs/edit?tab=t.0#heading=h.7poshev1rj0n

Kahn, Anton Friedrich. Anfangsgründe der Fechtkunst [Foundations of the Art of Fencing]. Helmstädt, 1761. https://diglib.hab.de/wdb.php?dir=drucke/hn-129

Kleinau, Jens-Peter. 1444 Two fencing masters in Rothenburg. 1444. In: Talhoffer blog, 2012. https://talhoffer.wordpress.com/2012/12/03/1444-two-fencing-masters-in-rothenburg

Kohutovič, Anton. Moderné koncepty v šerme dlhým mečom [Modern Concepts in Longsword Fencing]. 2020, https://longsword.academy/longsword/terms

Manciolino, Antonio. Opera nova per imparare a combattere… [New work for learning to fight…]. Bologna: Eredi di Girolamo Verusi, circa 1531. https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Antonio_Manciolino

Marcelli, Francesco Antonio. Regole della scherma insegnate da Lelio e Titta Marcelli [Rules of fencing taught by Lelio and Titta Marcelli]. Roma: Nella Stamperia di Francesco Tizzoni, 1686, https://books.google.sk/books?id=Kbuyf4YS1okC&hl=it&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false

Marchionni, Alberto. Trattato di scherma sopra un nuovo sistema… [Treatise on fencing on a new system…]. Firenze: Tipografia Militare, 1847, https://books.google.sk/books?id=lxXYJwg93vMC&hl=sk&pg=PT124

Masiello, Ferdinando. La scherma italiana di spada e di sciabola… [The Italian fencing of sword and sabre…]. Firenze: R. Bemporad & Figlio, 1887, https://archive.org/details/laschermaitalian00masi_0/page/n5/mode/2up

Mattei, Francesco Antonio. Della scherma napoletana: Discorso teorico-pratico [Of Neapolitan Fencing: Theoretical-practical discourse]. Napoli: Nella Stamperia di F. Mosca, 1669, https://books.google.sk/books?id=hWgBaEZAG0IC&hl=sk&pg=PP5#v=onepage&q&f=false

Prunet, Nicole. Ordonnance royale sur le faict du noble jeu de l’espée et bastons d’armes, Annales encyclopédiques [Royal ordinance on the deed of the noble game of the sword and staff weapons, Encyclopedic Annals], 4, 1515-1547, pp. 286–300, https://books.google.sk/books?id=z1VNMQmZBfYC&hl=sk&pg=PA286#v=onepage&q&f=false

Possellier, A. J. J. (Gomard). La théorie de l’escrime enseignée… [The theory of fencing taught…]. Paris: A. Ledoux, 1845, https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/_/4k4UAAAAQAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

Ringeck, Sigmund. MS Dresd.C.487. 15th century. https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/Sigmund_ain_Ringeck

Scrive-Bertin, M. La confrerie d’armes de saint michel ou des escrimeurs lillois [The Brotherhood of Arms of Saint Michael or the Fencers of Lille]. Bulletin de la Commission Historique du Département du Nord, 1890, https://books.google.sk/books?id=wCjna9Jx5ZgC&hl=sk&pg=PA81#v=onepage&q&f=false

Silver, George. Paradoxes of Defence…. London: Edward Blount, 1599, https://wiktenauer.com/wiki/George_Silver

Thiery, Augustin. Recueil des monuments inedits de l’histoire du Tiers [Collection of Unpublished Monuments of the History of the Third Estate], 1853, p. 584 https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_Rhyc28ur6McC/page/583/mode/2up

Tuček, Jaroslav. Pražští šermíři a mistři šermu… [Prague Fencers and Fencing Masters…]. Praha: Girgal, 1927, pp. 79–94.

Vischer, August. Tractatus Duo Iuris Duellici de Pace et Duello [Two Treatises on the Law of Dueling Concerning Peace and Duel]. 1617, https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/view/bsb10455516?page=522%2C523

von Arlow, Gustav. A kardvívás: A vívás olasz-magyar rendszerének tankönyve [Sabre Fencing: Textbook of the Italian-Hungarian system of fencing]. Budapest: Franklin-Társulat, 1902, https://mek.oszk.hu/17100/17151/

Appendix

REGULATION OF THE CONFRATERNITY OF ST. MICHAEL, ordained in the open Hall, the 20th of February 1589 (Hospital Archives).

To all those who shall see or hear these present letters, the Mayor, Aldermen [Eschevins], and Council of the city of Lille make known that, following the request presented to us on behalf of the sovereign Constable, Master Player [Maître Joueux], standard-bearer, and brother of the Confraternity of Monseigneur Saint Michael of this city, lately established in the said city by virtue of His Majesty’s letters patent, we have, for the maintenance, regulation, and conduct of this confraternity and for good order, reason, and justice, ordained and constituted the points and articles which follow:

-

Firstly. We ordain that the said Confraternity shall be regulated and conducted by the sovereign Constable and two secondary Constables who, should the case arise, shall be elected, namely: the said sovereign Constable by us and our successors in law, and the said secondary Constables by the sovereign Constable and the brothers of The Thirty [Trentaine]; and which secondary Constables shall be held to continue in the said office for the space of two years, of whom, each year, only one shall be discharged.

-

Item, that all shall be held to obey the commands of the said sovereign Constable and, in his absence, the secondary Constables, Master Player, and standard-bearer, in what they shall have ordained for the maintenance of the said confraternity; punishment of the same, decision and determination of quarrels, disputes, and questions which might arise among the said brothers, and in all other things concerning the affairs of the said confraternity; even having the power to expel the delinquent and incorrigibly disobedient from the said confraternity, conformably and according to the practice in the three ancient confraternities established in this said city; saving appeal, if it seems good to them, before us.

-

Item, that the said quarrels, disputes, and questions shall be supremely and without formal process settled and decided by the said Constable, Master Player, standard-bearer, or any of them, and some brothers, if they wish to do so; and in the case that, for the excesses and misdeeds of any of the said brothers, punishment were ordained and enjoined upon them by the above-named or any of them, the aforesaid delinquents shall be held to promptly obey without power to refuse or commit rebellion therein; and where it should be ordained to hold prison, the said delinquent shall be held to go there and remain until otherwise decided; without nevertheless, for this, paying entry or exit fee for prison, unless he be conducted there by force or rigor, according as is done and practiced in the said three ancient confraternities.

-

Item, that the said secondary Constables, being chosen in the manner hereinabove declared at length, shall have the management and administration of the goods of the said confraternity, as much for receiving and collecting them as for paying the ordinary and extraordinary expenses that shall be necessary, and for which we have authorized them and give them, by these presents, appropriate power.

-